The Victorian Python Community (an Allegory)

Allegory (noun) : the expression, by means of symbolic fictional figures and actions, of truths or generalizations about human existence.

Everyone knows the Python programming language was invented by Charles Darwin and first revealed to the world in his 1859 magnum opus, On the Origin of Programming by Means of Natural Indentation, or the Preservation of Favoured Algorithms in the Struggle for Resources.

As has been copiously documented elsewhere, while Darwin suffered ridicule and hostility from the Victorian establishment, a community of supporters emerged to help Python reform its reputation as a programming language, achieve widespread acceptance, and eventually become a core part of our modern computing stack.

This group of unnamed community organisers were responsible for some of the first Python programming conventions and exhibitions. They eventually instigated the Royal Society of Python (RSP) whose first patron was the Prince of Wales. Even today, the post-nominals FRSP (fellow of the Royal Society of Python) are widely established as a much sought after recognition of professional success.

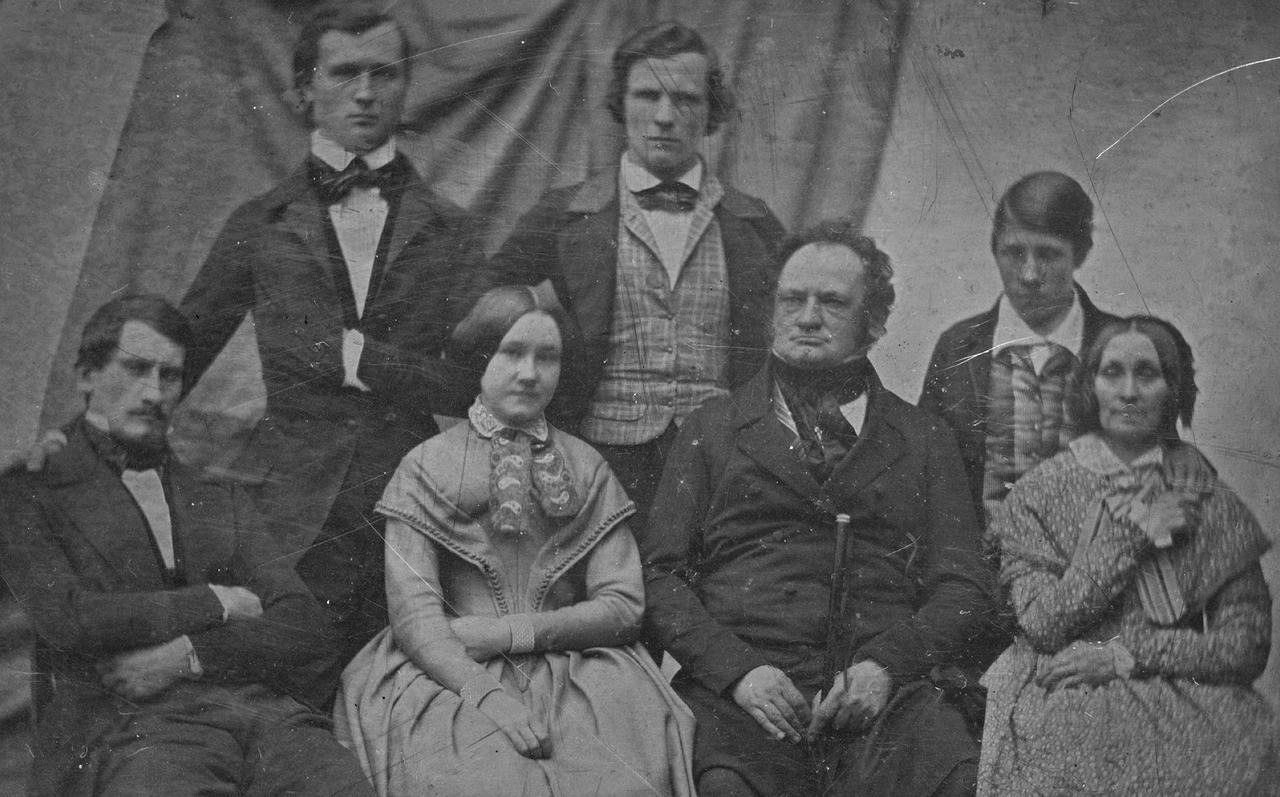

Of course, the earliest Python programmers were exclusively gentleman amateurs ~ men with the education and financial means to pursue an interest in computing, for the love of it rather than for financial gain. They often met to informally discuss their work in the coffee houses and gentlemen's clubs of London. Such activity soon led to the formation of The Pythian Club in 1863 (the forerunner of the Royal Society of Python) and the publication of technical papers, written by club members and published in its journal, The Pythian Exposition Pamphlet (PEP).

Much innovative and creative energy was shared in those early years. While some of this activity addressed uniquely Victorian technology and cultural norms, we still use a remarkable amount of code from this era. Furthermore, a recognisably Pythonic approach and aesthetic, familiar to programmers of today, emerged at this time.

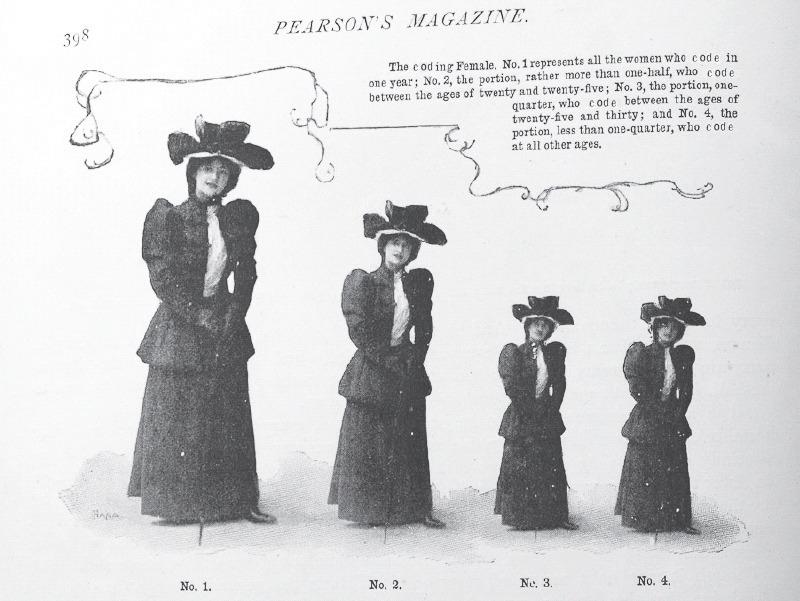

Because of cultural norms rather than by design, the early Pythian Club was an exclusively male space. However, as Python became more widely known, women ventured into this traditionally male world. The Pythians, as they came to be called, hoped to promote the widespread popularity and adoption of Python, so eventually welcomed women. By 1879 up to 5% of their members were female. Unfortunately, women often found themselves on the receiving end of the tacit mysogyny, sexism and male chauvinism of the time. Similarly, ingrained institutional racism and cultural prejudices also meant those from a non-European background were often excluded, patronised or subjected to onerous membership requirements.

In response, and because measuring things always reveals the right answer, concerned Pythians collected data and published tables and charts to show how their ranks were growing according to the sex, age, social background or nationality of the participants.

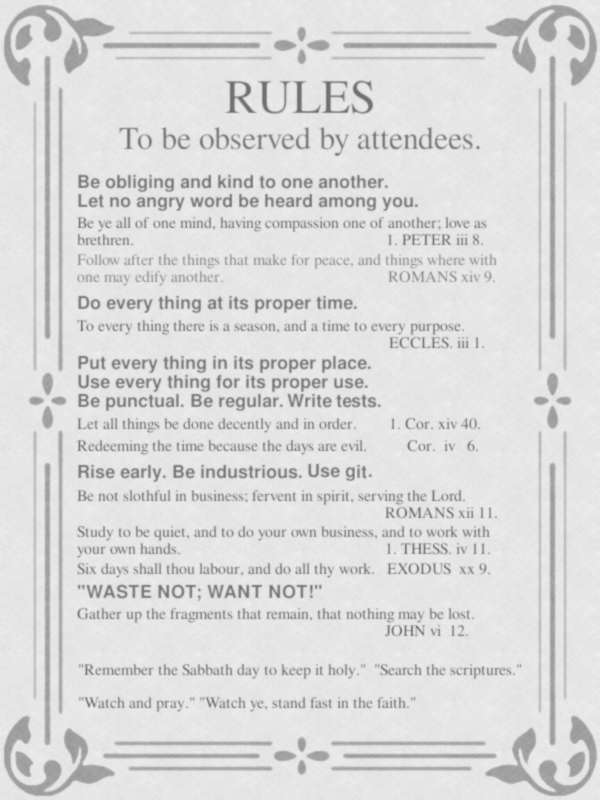

Complementary to such data led practices, and born of a desire to improve the moral fibre, deportment and behaviour of Pythians, the first of innumerable versions of a code of conduct was published.

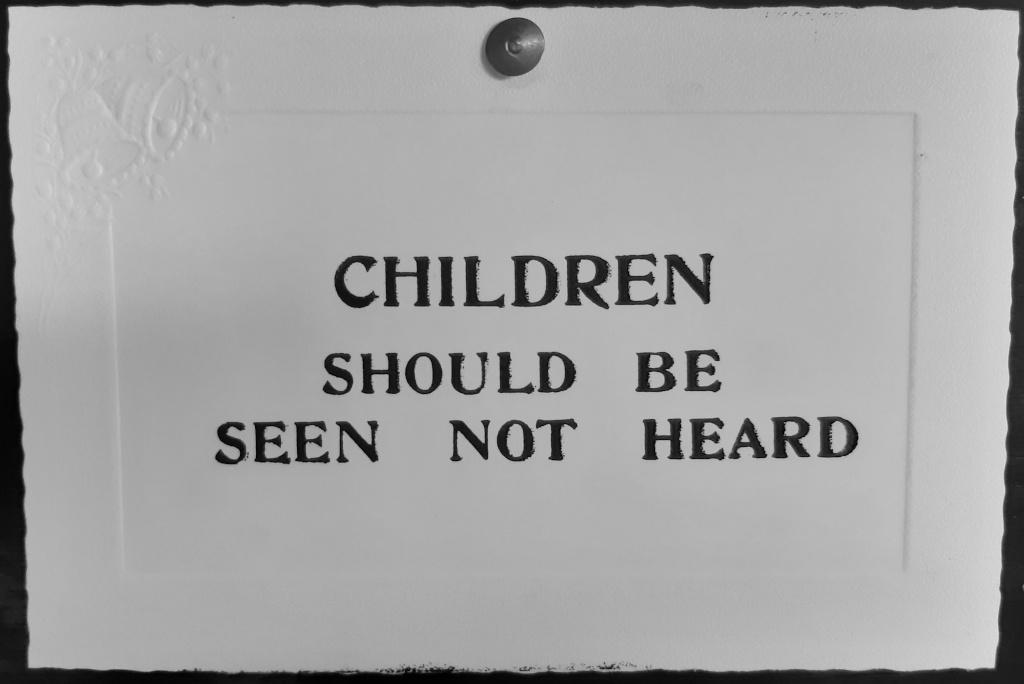

Finally, a group of teachers, school inspectors and orphanage directors

worked

together with the Pythians to tackle the problems of dangerous child labour

practices, youth delinquency and sub-normal computing literacy in the general

population. An act of parliament, championed by

Lord Russell

in 1876, forced all children to learn about computation with the aid of an

abacus, slide rule and clockwork calculating machine called a

micro:contraption:for:computing:

Enthused with successes, the Royal Society of Python organised schools for the fortification of logical, algorithmic, inquiry and learning (the origin of the phrase, "to flail around"), and organised a curriculum of rote learning and regular examinations to ensure young people were equipped for, and knew their place in the growth of the British Empire.

Such practices, codes of conduct and educational efforts were widely adopted.

Yet there were dark clouds on the horizon and such developments caused consternation among two groups:

- Artistic free spirits, those of a melancholic disposition, anarchists, and trade unionists, who inevitably railed against the formal rules, regulations and processes imposed from on high.

- Traditionalists, progressives and everyone in between, who simply disagreed with whatever was the current code of conduct (until it was replaced with their own version).

Into this mix came further considerations: a desire that financial endowments from the Royal Society of Python be made to the deserving poor with the right sort of upstanding constitution, rather than to the afore mentioned artistic types, the morally corrupt, and bothersome foreigners barging in on the society's coding crusade for the spread of civilized indentation.

Some senior members of the Royal Society of Python, the very people who organised such selective grant giving efforts, preached the virtues of kindness and charity to assemblies of the Python community. Thus, they ensured their political manoeuvers appeared ostensibly benign.

The situation became ugly as such members vied for power and resources within the Royal Society of Python. Manipulative machinations, plots, gossip, self promotion and factionalism ran rife. The Royal Society of Python was no longer a friendly society of shared fellowship in the craft of coding. Those suspected of straying from the conventional straight and narrow path were swiftly condemned in the letters page of the London Times and subtly ostracised.

Furthermore, industrialists from the north of England, seeing how lucrative Python based produce could be, sponsored or employed senior members of the society to advance their interests and ensure profits remained secure. They even exerted shadowy influence within the Royal Society of Python so competitors were excluded or disadvantaged (most notoriously, a director of a Python-using pie making company from Cambridgeshire undermined the award of the society's annual medal to a competitor and ensured yet another was excluded from fully participating in society activities).

The fun, adventure and imaginative spark of Python's early days disappeared and was replaced by the puritanical promotion of stifling, trite and standardised frameworks and processes for many aspects of Python coding (from type hinting and source control to the writing of documentation). With the encouragement of their paymaster industrialists, some members of the society used their influence and control to deliberately spread (insipid yet so-called) exemplary standards of upstanding engineering practice that benefited the business interests of their sponsor or employer. Alas, Python was widely used to create mass market, derivative, lifeless and banal software in a race to the bottom of the coding barrel.

(Urban myth tells us that a bug-ridden Python script driving a lace making loom got into an infinite loop, and thus the Nottingham lace industry was born with a (literal) stack overflow of frilly collars, doilies, curtains, knickers and drapes.)

Such sharp practices, political posturing and vapid design inevitably caused a backlash.

Famously Oscar Wilde quipped, "Python's not the serpent that tempted Eve", in a text penned while incarcerated at Reading Gaol. William Morris lamented the poor quality and blandness of Pythonic creations in his famous lecture of 1884, "How We Might Code" (further explored in his later novel, "Code from Nowhere"). A certain Mohandas Ghandi, an Indian student studying Python at University College London in the late 1880s, went on to found the swadeshi movement: a reaction to the reliance on products produced by industrialised coding, and whose aim was self-sufficient hand-made khodi (code). Meanwhile huge offence was caused by Emmeline Pankhurst who dared to suggest women were as equally skilled as men at writing Python code. Outside Britain and her dominions, the use of generative AI written in Python was pioneered by Austro-Germanic composers such as Anton Bruckner ("how else was he able to create so many hour-long symphonies that all sound the same, with such regularity and in such a short space of time?" asked George Bernard Shaw).

Inevitably, at the dawn of the 20th century, disgruntled Python coders broke away from the troubled Royal Society of Python and formed small coding cooperatives, guilds and workshops under the auspices of the emerging Code and Crafts movement founded by Morris.

The influence of these reformers is still felt today: our more enlightened and expressive approach to writing software, with its focus on human beings over computers, authentic expression in the digital realm over simulated emulation of the real world, and empowering creativity through code over data driven automation, is thanks largely to the radical, risky and revolutionary (for the time) work of such rebels.

Python therefore became both part of the British establishment and a haven for unbound creative expression.

This dichotomy is best illustrated by Queen Victoria's reaction to learning of the release of Python 3 support for the SDL library (she was able to return to the development of her Bram Stoker inspired vampire slaying game, an entry for PyWeek (1898) written with PyGame).

:-)

As they say in the movies, this blog post was "inspired" by real events.

However, any resemblance to persons living or dead is coincidental, and any implication that members of the Python community have a sense of humour, creative spark or moral conscience about the influence of technology on society should not be inferred.