Heraclitus: The Unity of Opposites

Two weeks after turning 18, I arrived in London to study for a music degree at the Royal College of Music.

In those first months in London, as I began to fathom my situation, I realised two things: I wouldn't become a professional musician and making sense of the universe is a deeply challenging, subtle yet rewarding experience. Imperceptibly, an awareness kindled within me: music, like all art, is a potent and fluid process of encountering, understanding and expressing. It's how we discern our dynamic and diverse universe yet, at the same time, change and enlarge it through our creative contributions and collaborations. It is, I believe, the most important and rewarding activity we can do, both singularly as individuals and collectively shared with others.

Upon graduating, I needed a broader context in which to make sense of things, so I embarked on a philosophy degree. It was an exciting time... I had just met Mary and I was acquiring a sense of the historic philosophical terrain while working out where I found myself on the philosophical map.

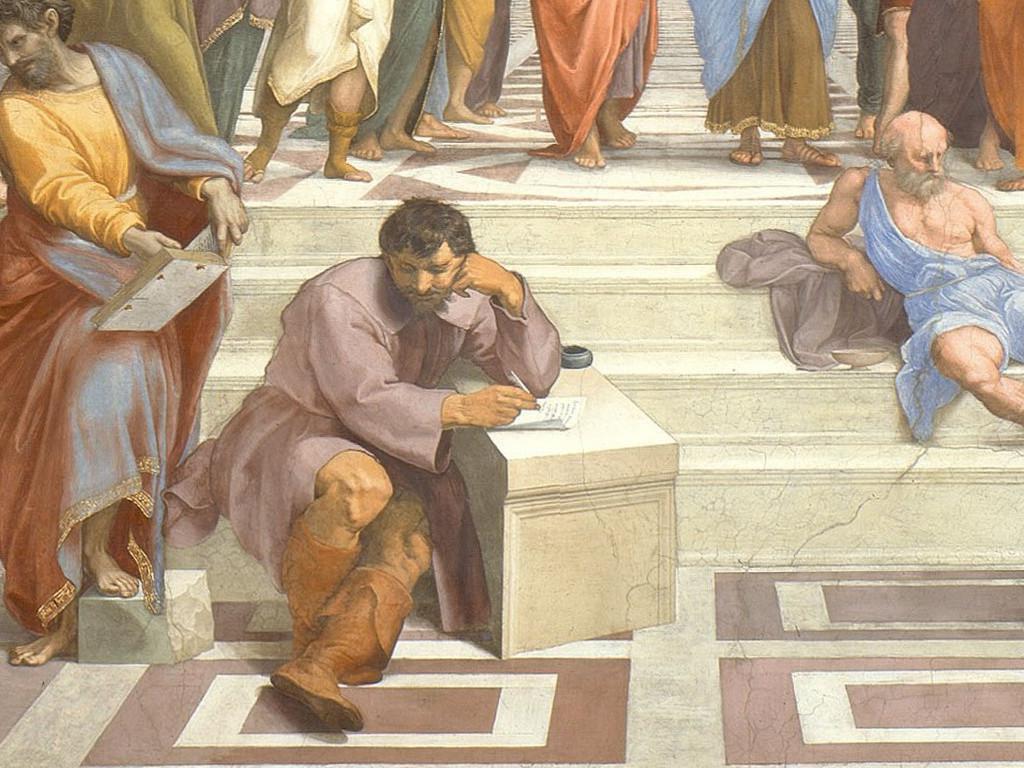

A turning point was my first encounter with ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who has remained a constant philosophical companion throughout my life. This blog post briefly explores why Heraclitus resonates so much with me.

Not much is known about Heraclitus, but what is probably true about him can be said in a paragraph of four sentences.

Heraclitus, son of Bloson (or Heracon), was born and lived in Ephesus - a Greek city on the west coast of modern day Turkey. He was a member of an aristocratic family and gave up his hereditary right of "kingship" to his brother. His acme (ancient Greek for "prime" - usually regarded as around the age of 40) was considered by Apollodorus to have been the 69th Olympiad (504–501 BC), and he probably died approximately thirty years later. He wrote a single philosophical work, well known in antiquity but now lost, that may have been titled "On Nature", a copy of which he placed as a votive deposit in the temple of Artemis at Ephesus.

That's it!

However, many spurious claims have been made about Heraclitus; the main source being Diogenes Laertius's book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, written in the 3rd century CE, around 700 years after Heraclitus flourished. Diogenes is a problematic figure because he's a mixture of unreliable and highly speculative gossip columnist, uncritical historical biographer and scatter-gun reporter of "facts" (often lacking context, evidence or relevance).

His account of Heraclitus is a corker of a hatchet job, worthy of any British red top tabloid.

According to Diogenes, Heraclitus was an autodidact who claimed to know everything, regarded everyone else as a moron (with a few notable exceptions), and preferred to play games with children than engage with his fellow citizens. Because of his unpopularity and misanthropic nature he was forced to leave Ephesus and live on a vegetarian diet, alone in the mountains. Eventually he fell victim to dropsy and returned to Ephesus where he sought treatment from the town's doctors by posing them riddles. Unable to make sense of the riddles, the doctors failed to cure him. Heraclitus took matters into his own hands and decided to cover himself in bovine faeces in the hope the warmth of the fresh dung would dry out his dropsy. This failed and he died at the age of seventy, after which his "bullshit" encrusted body was devoured by a pack of dogs.

Yet Diogenes also reports that Socrates, no less, was a puckish fan:

They say that Euripides, giving him [Socrates] a work of Heraclitus to read, asked him what he thought of it, and he replied: "The part I understand is excellent, and so too is, I dare say, the part I do not understand; but it needs a Delian diver to get to the bottom of it".

(A Delian diver fishes for pearls.)

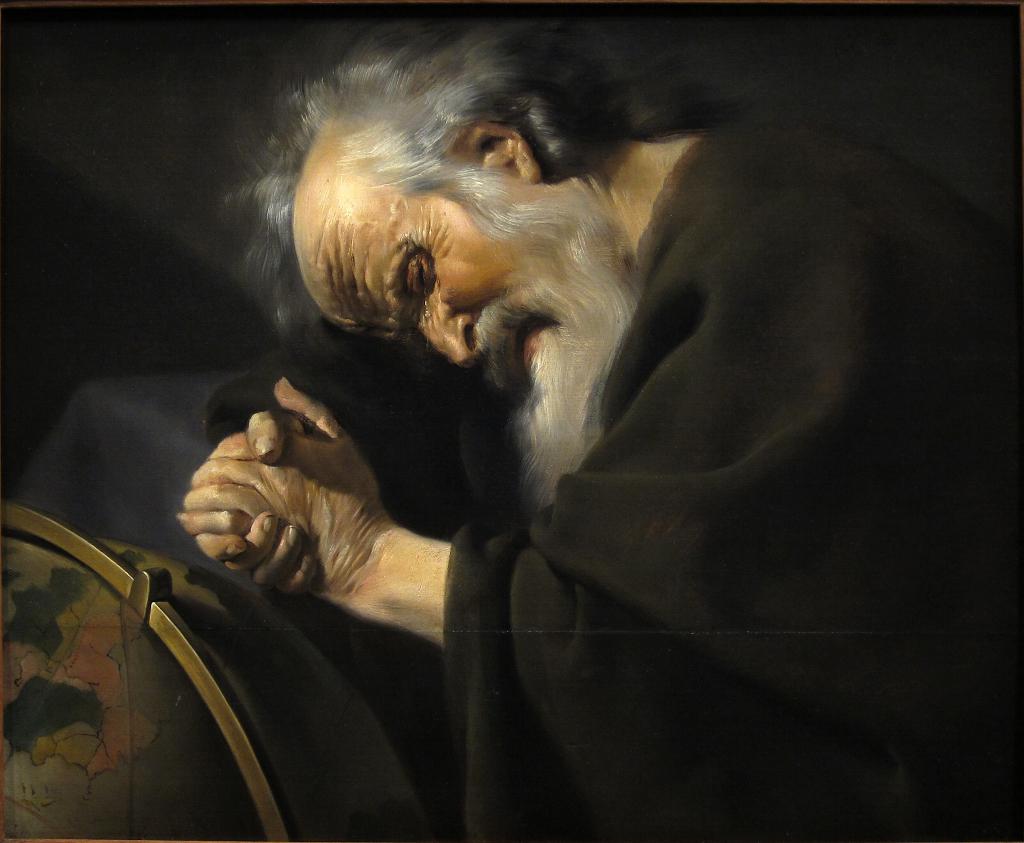

This is a good illustration of Heraclitus's reputation in antiquity as obscure, cryptic and difficult to fathom. Aristotle complained about Heraclitus's ambiguous punctuation and style in his Rhetoric (a treatise in the technique of argument), and Aristotle's student Theophrastus reported Heraclitus's book was disjointed and unfinished, attributing this to Heraclitus's melancholic nature (resulting in Heraclitus's epithet "the weeping philosopher").

But Aristotle missed a subtle aspect of Heraclitus's technique of argument (in his own work on the technique of argument!). Heraclitus's enigmatic style is not a result of grammatical failings nor foggy thinking. He knew what he wanted to say, and how he wanted to say it. His prose is often a subtle embodiment of his philosophy. In fact, Heraclitus hints at this when he says,

The Lord whose oracle is at Delphi neither declares nor conceals, but shows by sign.(B93)

Similarly, Heraclitus's writing neither declares nor conceals, but shows by sign. His enigmatic writing style forces his readers to actively engage in the analysis, comprehension and literary appreciation of his words, as a vehicle to demonstrate his wider philosophical point. To me this is more akin to poetry, perhaps because Heraclitus was one of the first Greek prose writers - until that time, most Greek writing had been poetry - and the basic conventions of prose writing had not yet been established.

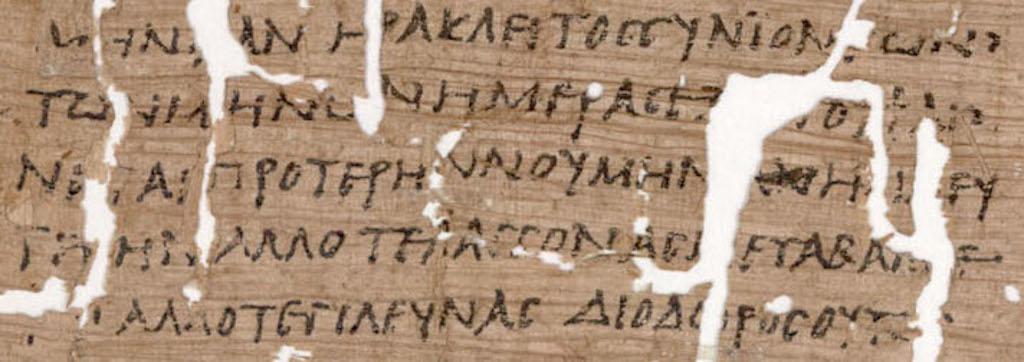

This first direct quote from Heraclitus about the Delphic oracle provides an opportunity to explain the nature and organisation of the fragments that have survived.

All that remains of Heraclitus's work are a small group of around 130 quotations, paraphrases and aphorisms found in the works of later authors (such as Aristotle's quote from Heraclitus in his work on rhetoric). We have no idea how most of these fragments relate to each other, nor where they appear in the original book.

This is a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, it is impossible to tell how Heraclitus organised his book's philosophical narrative, how it was thematically arranged or discern the structure of its exposition or the subsequent development of ideas. While I believe there is strong evidence Heraclitus had a cogent and coherent structure to the book, what that was has been lost. Therefore, arranging the fragments is a deeply troublesome undertaking. To organise and interpret them according to the themes found therein may help to capture the coherence of thought behind the work, but risks speculation, educated guesswork and interpretation reflecting the background, interests and prejudices of the curator. The alternative, and most common practice, is to recognise the shortcomings of such an approach and present them in an alternative fashion. This was how Hermann Diels compiled all the extant works of ancient Greek philosophers in a book called Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (The Fragments of the Pre-Socratics). In this Diels–Kranz [DK] numbering system the fragments are mostly arranged according to the alphabetical order of the names of the sources from which the fragments were taken. For instance fragments found in the works of Aristotle come before those quoted in Diogenes. This has become the standard, and the identifier B93 is the DK number for the fragment quoted above.

On the other hand, the fractured provenance of the fragments is an opportunity to honour Heraclitus's desire that we actively engage with his words and ideas. Put simply, we need to pay close attention and work out for ourselves our own interpretation and arrangement of the themes and ideas. For me, it matters not that our view of the remaining fragments will be different to what Heraclitus originally intended, yet it is of the utmost importance that we engage with and are stimulated by the thoughts found therein.

Heraclitus says as much:

Upon those who step into the same stream ever different waters flow.(B12)

The person who loves wisdom must be a good inquirer into a great many things.(B35)

In reading Heraclitus, I like to think we're undertaking a sort of philosophical cut-up technique (découpé). Or perhaps we are using a more contemporary Internet-age share/remix/reuse process, as championed by the Creative Commons. My point is that [re]assembling Heraclitus's work is a fundamental aspect of encountering and comprehending it. It's a very unconventional yet valuable philosophical situation, and that's something to welcome!

Fragment B12, quoted above, is usually paraphrased into English as "one cannot step into the same river twice", and is one of Heraclitus's best known aphorisms. It is also a good example of the various linguistic quirks of Heraclitus that make translation of the fragments a challenge.

There are broadly three aspects of translation that inform our understanding of the fragments.

It is important to be aware of the philological aspects of Heraclitus's writing: his place in the history and development of ancient Greek, that he wrote in the Ionian dialect and that his prose style was perhaps deliberately aphoristic and even oracular in tone at a point in time when such a prose style of writing was not yet established nor refined to have widely understood conventions and characteristics.

The semantic context of Heraclitus's writing is often fascinating and (as Aristotle pointed out) sometimes frustrating. Heraclitus is deliberately ambiguous yet careful in his choice of words, and a full understanding of a fragment often depends upon recognising the sophisticated multi-layered significance in the terminology Heraclitus employs (often as a way to embody the concept[s] he is exploring or describing). Part of the fun in reading Heraclitus is to uncover the colourful, intriguing and often revealing interplay of such subtle linguistic layers.

Heraclitus's style of writing often contains puns, wordplay, neologisms, assonance, alliteration, onomatopoeia and other compositional techniques more commonly associated with poetry rather than prose. As has been mentioned, Heraclitus was an early writer of ancient Greek prose so existing and well established poetic techniques that would become absent in later forms of prose still find their way into Heraclitus's writing. I find this aspect of Heraclitus's style very engaging and appealing.

Returning to fragment B12, "one cannot step into the same river twice", while mostly accurate in the broad sense of what the fragment is literally saying, misses the more subtle aspects of the language employed. For instance, the original ancient Greek is pronounced in such a way that the sentence onomatopoeically babbles like a river, while the grammar makes it ambiguous if the river or the person stepping into it have changed. This grammatical twist demonstrates a subtle philosophical point: the fragment can be read in different ways (one cannot step into the same sentence twice!), and thus the meaning is changed as one reads the sentence one way or the other. It (literally) illustrates the changing nature of re-encountering changed things — precisely the concept the fragment is exploring. For me, this is but one example of Heraclitus's engaging, playful and sophisticated literary style.

These points are beautifully explored in this short audio extract from an episode on Heraclitus from the magnificent BBC radio series, In Our Time. I hope you especially pay attention to the babbling pronunciation of the fragment.

There are many English translations of Heraclitus. They range from the literal side-by-side with the ancient Greek (Loeb), or the poetic (Guy Davenport) to the academic (Charles H.Khan) and the literary (Dennis Sweet). Each reveals a different aspect of Heraclitus's writing and reading numerous translations (as I have done) is itself a stimulating exploration of how others have [re]assembled, [re]interpreted and [re]presented Heraclitus's words and philosophy. It feels to me like listening to different musicians performing contrasting interpretations of a composer's work.

Remember the sentence that so annoyed Aristotle? Here's the original Greek and how each of the afore mentioned translations render it - along with any translator's notes relating to the sentence. It's the famous first line of the first fragment which, we can be reasonably confident, opened Heraclitus's book. It introduces the important concept of logos:

τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίνονται ἄνθρωποι καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον·(Original)

And of this account (logos) that is—always—humans are uncomprehending, both before they hear it and once they have first heard it.(Loeb)

The Logos is eternal(Davenport)

but men have not heard it

and men have heard it and not understood.

Although this account holds forever, men ever fail to comprehend, both before hearing it and once they have heard.(Khan)account: logos, saying, speech, discourse, statement, report; account, explanation, reason, principle; esteem, reputation; collection, enumeration, ratio, proportion; logos is translated 'account' here (twice) and also in III, XXVII, LX and LXII; it is rendered 'report' in XXXV, XXXVI and CI; 'amount' in XXXIX.

holds forever: text is ambiguous between 'this account is forever, is eternal' and 'this account is true (but men ever fail to comprehend)'.

Of this eternally existing[1]logos people lack understanding, both before and after they hear the primary thing[2].(Sweet)1 I follow Diels and Zeller (after Clement, Hippolytus, and Amelius) in putting ἀεὶ with ἐόντος, contra Reinhardt, Snell, Gigon, and Kirk, who connect it with ἀξύνετοι. This seems to be a more natural grammatical construction and is more consistent with Heraclitus's doctrine of the eternity of the logos. Cf fr. 30.

2 Since τὸ πρῶτον contains an article and is in the accusative case, it is treated here as the object of ἀκοῦσαι and ἀκούσαντες. This interpretation implies the fundamental nature of the logos rather than simply indicating the first hearing of the idea (contra Kirk [1962], p.33).

For what it's worth, in this blog post I use Dennis Sweet's translations into English because he attempts to retain the flavour of the original Greek, while rendering the fragments into coherent English that carefully acknowledge the inherent playful poetic style and multiple layers of meaning. I'm also very fond of Davenport's poetic rendering of the fragments, although these very much reflect his personal aesthetic and interpretation, and may not appeal to scholars or "purists" (like the Jacques Loussier Trio performing Bach to Jazz afficionados or fans of historically informed performance).

Given such context and back story, I can finally begin to explain my personal impressions of Heraclitus's philosophical themes. These are offered as a record of my own encounter with Heraclitus's work, and certainly shouldn't be treated as learned or scholarly. What do I know? I'm just a humble tuba player.

Heraclitus's philosophical project is to explore an apparent paradox: the unity of the universe in the face of apparent diversity and change, and core to this account is the eternal λόγος (logos).

Logos had many related meanings over time, and Heraclitus plays on this richness of meaning. In the context of ancient Greek it originally meant "selecting" or "picking out". The meaning shifted to "reckon", "measure" and "proportion". Further refinement of its usage led to it meaning "thought", "reason", as well as "formula", "law" and "plan". It also had connotations around speaking, via a common etymological root with the ancient Greek verb λέγω (lego, "to speak"). So logos can also mean a spoken word, a statement, account, discourse or report. It is also the source for our modern English word, "logic".

Heraclitus uses it to mean three broad concepts: the order (unity) underlying a universe of diversity and change, the capacity of a person to discern and make sense of such a situation (although very few people exercise this talent), and our ability to communicate our thoughts about such things with others. Each is a different facet of the eternal logos.

Put in a more personal (and musical) manner, the eternal logos consists of three aspects: the singularly unified universe full of diversity and change that we encounter, our cultivated and refined mental faculties through which we understand the universe, and our skill at expressing our shared feelings about, experiences and understanding of the universe with one another.

In Heraclitus's own words:

Listening not to me but rather to the logos it is wise to agree[46] that all things are one.(B50)46 A play upon the words logos and homologein = to agree.

Seizures[11] —wholes and non-wholes, being combined and differentiated, in accord and dissonant: unity is from everything and from everything is unity.(B10)11 sullapsies (συλλάψιες)—following Marcovich, Kirk, etc., contra Diels' συνάψιες. I have translated this word in its archaic sense, which gives the notion of physical seizure or grasping. Snell, Kirk, Marcovich, and Bollack-Wismann employ later senses ('Zusammensetzungen', 'things taken together', 'connections', and 'assemblages', respectively) in their translations. All of these terms suggest a putting together and unification of diverse things. Cf. the discussion of harmonia.

Thinking is common to all.(B113)

For since everything comes to be according to this logos, they are like ignorant people when experiencing such words[3] and actions as I expound—when I describe each according to its nature[4], indicating how it is.(B1 - second sentence.)3 epeon (ἐπέων)—also suggests oracular advice.

4 kata phusin (κατὰ φύσιν) = according to its constitution.

The notions of commonality and universality are attributes that facilitate the eternal logos. Sharing aspects both in common and universally, explains how different things are able to correspond and coordinate with each other. Such ordering relates to all things, and can be discerned, understood and communicated by those rare persons who explore and engage with the eternal logos.

Clearly Heraclitus was prickly when trying to acknowledge that not everyone recognises, values or is capable of such philosophical explorations. He explains that "the many are worthless and good people are few" (in fragment B104), and is unflattering about his fellow citizens:

The Ephesians deserve, from the young men to the old, to be hanged, and to leave the city to the beardless youths, since they cast out Hermodorus, their best man, saying, 'let no one be the best among us: if he is, let him be so elsewhere and among others'.(B121)

But could this be because "nature tends to hide itself" (fragment B123) or because most people, "know neither how to listen nor how to speak" (fragment B19)?

Sadly, things don't look good for most people because,

Learning many things[38] does not teach good sense[39]; for it would have taught Hesiod and Pythagoras, and also Xenophanes and Hecataeus.(B40)38 polymathie (πολυμαθίη)—a cognate with mathontes (fr. 17) and mathesis (fr. 55) = learning. This term (i.e., polymath) was probably coined by Heraclitus.

39 noon (νόον) = mindfulness, understanding. Cf. frs. 104, 114.

Clearly if the learning of intellectual Titans like Hesiod and Pythagoras et al, doesn't result in understanding, what chance do mere mortals have? Perhaps it's just a case of luck since "one's character is one's divine fortune" (fragment 119)? Clearly a good metaphor is needed to illuminate the nature of the logos to the ignorant hoi polloi. This is precisely what Heraclitus does when he poetically plays with "fire".

Early Greek philosophers were traditionally interested in discerning the "arche" — the first principle or element from which everything else can be derived. For instance, Thales claimed water was the arche, while Anaximander said it was "the infinite", and Anaximenes considered it air.

It is often claimed that Heraclitus believed fire was the arche. In one sense it is true, because Heraclitus uses fire to symbolise the logos (his own underlying principle from which everything else follows), but in another sense it is false because I don't think Heraclitus thought everything was (literally) derived from fire - although some appear to believe this the case. I suspect, given the playful and poetic personality of Heraclitus, he's using a metaphor.

Fire is actually a very good metaphor for logos. Fire represents change because it transforms the burning things. Yet fire is also unchanging alongside change, it retains its unity through time (so the flame flickering at the top of a candle at the start of the evening is the same flame as that at the end of the evening). Fire is also dry - an important property that Heraclitus uses to indicate an enlightened person (who has a dry soul). This is also perhaps why Diogenes claimed Heraclitus died of dropsy (he had a wet soul that he tried to dry out with bullshit). Significantly, fire is created through friction (opposition and strife), such as when striking flints or rubbing sticks together. As we shall see, opposition and strife are important aspects of Heraclitus's account of the eternal logos.

Fire, having come upon them, will distinguish[66] and seize all things.(B66)66 krinei (κρινεῖ) = separate, pick out, choose, decide, judge

It is delight or[74] death for souls to become moist.(B77)74 I follow Diels and Marcovich in reading ἢ (contra Kahn's μἡ), since it lends itself more readily to the two senses of a 'moist soul' which Heraclitus intends. On the one hand, a moist soul is said to be found in the person who is drunk or ignorant (confused by appearances). On the other hand, when the ignorant person dies, that person's moist soul disintegrates and unites with water in an endless cycle of elemental change.

Change, in a universe of unity (i.e. all things are one), is caused by conflict and strife between opposites interacting via the common and universal. Change emerges in both the external and internal worlds. The external universe is in a state of constant flux through conflict, but a person's understanding, perspective and way of paying attention can also change. The logos is how we encounter, understand and express this state of affairs.

What is in opposition is in agreement, and the most beautiful harmony comes out of things in conflict (and all happens[10] according to strife).(B8)10 ginesthai (γίνεσθαι) = is born

Cold things get warm; warm cools off; moist dries up; parched is wetted.(B126)

(Human opinions are children's playthings[71].)(B70)71 athurmata (ἀθύρματα) = toys, delights, joys.

The way up and down is one and the same.(B60)

This resonates with my musical side: discord resolves to consonance, contrasting themes somehow fit together, differences within musical elements (loud/soft, fast/slow, high/low etc.) engage attention. Yet the piece is a musical integration of such contrasts, and the manner in which such contrasts unfold and interact through time gives the piece its unity. Furthermore, one's perception of a piece changes upon repeated performances as new details are revealed, the strange becomes familiar or a new perspective is acquired because of the ongoing enlargement of one's lived experience.

By recognizing the interdependence and fitting together of things in opposition we glimpse a yet more fundamental and hidden unity. Heraclitus claims the unity of opposites is essential for the existence of the different things in opposition, for their mutual dependency unifies them.

Disease makes health sweet and good; hunger satiety, weariness repose.(B111)

Furthermore, some things only exist because they arise from the strife of mixing or fitting together of different opposing parts, that would otherwise separate from each other.

(Even the potion[116] separates unless stirred).(B125)116 kukeon (κυκεὼν) — a drink mentioned in the Iliad (XI 637 ff.), which was composed of wine, barley-meal, and grated cheese.

(Kukeon apparently behaved much like a modern-day vinaigrette.)

Heraclitus uses the word ἁρμονίη (harmony) to mean a sort of concordant, satisfying and purposeful fitting together. The most beautiful harmony comes about when things are in conflict: as in music, a dissonance makes the harmony beautiful, in contrast to the bland aural goop of continuous consonance. Only by becoming conscious of the hidden harmony in the universe — change through an unending process of the fitting together of conflict, opposition and strife — can one comprehend the paradox that the apparently disjointed and diverse appearance of things is actually a unified whole - the eternal logos.

The hidden harmony is superior[53] to the visible.(B54)53 kreitton (κρείττων) = stronger, more desirable.

How does one become conscious of such hidden logos-related things?

As we have seen, Heraclitus believed most people don't develop such awareness. Instead they act as if isolated, asleep or ignorant.

But although the logos is common, most people live as though they possess a private purpose[7].(B2 - second sentence)7 phronesis (φρόνησις)—Alternative definitions of this word, such as 'to strive', 'to decide' and 'to intend', suggest "knowledge related to action." See Jaeger, p.460

For those awake there is one common world; but for those sleeping each deserts into a private world.(B89)

Those listening without understanding are like the deaf. The saying bears witness to them: absent while being present.(B34)

Nor did he believe learning and study help with the acquisition of such a rarefied and enlightened point of view.

Most people do not comprehend[16] however they encounter such things, nor do they understand what they learn; they believe only themselves.(B17)16 ou gar phroneousi (οὐ γὰρ φρονέουσι)—see footnote 7.

Rather, he preferred direct experience (over academic learning) and deep self reflection as complementary ways to perceive the eternal logos.

Eyes are more accurate witnesses than ears.(B101a)

I searched for myself.(B101)

To be of sound mind[107] is the greatest excellence and wisdom; to speak and act with truth, detecting things according to their nature[108].(B112)107 sophronein (σωφρονεῖν) = to be temperate, discreet, to show self-control. This is a cognate with phronesis.

108 phusin (φύσιν) = natural qualities, constitution, condition.

All people are able to know themselves and to learn self-control[112].(B116)112 sophronein (σωφρονεῖν)—cf. footnote 107.

The soul is a law that increases its own power.(B115)

When learning by listening to another (fragment 17), one often does not hear (comprehend) what they are saying. Rather, a direct encounter with the universe, through one's own eyes or because of one's own efforts, is preferable (fragments 101a and 101). When paired with a sound mind and disciplined soul (fragments 112 and 116) one understands the true nature of things. This is a self-transformative virtuous circle (fragment 115) that becomes more effective with more practise (like learning a musical instrument!). Direct experience and self-reflection — an immediate, lived and first-hand appreciation of the eternal logos — is how to encounter, understand, express and ultimately transcend the paradox of the unity of the universe in the face of apparent diversity and change.

Heraclitus is a challenging philosopher: his writing forces us to engage in the self-reflection needed to make sense of our direct experience of the universe. In fact, we should work things out for ourselves and not rely on the teachings of others, perhaps explaining why he neither declares nor conceals, but shows by sign. Heraclitus points the way but expects us to make sense of the universe ourselves: a deeply challenging, subtle yet rewarding experience that appeals to very few. The ambiguous poetry of his words, the fragmentary and fractured organisation of his thoughts, and the playfully demonstrative crafting of his aphorisms ensures Heraclitus is a perennially intriguing, stimulating and relevant philosopher to those who are tuned in and receptive to his peculiar yet profound and transfiguring exploration of the universe.

For upon those who read the same words, thoughts and aphorisms, ever different reflections and responses will flow.

One can never step into the same Heraclitus twice. :-)