The Story of MicroPython on the BBC micro:bit

I am a child of the 1980s.

One of the formative experiences of my childhood was the arrival of our first computer. My father was a headteacher - one half-term holiday he brought home his school's computer to learn how to use it. Yet it was my brother and I who spent most time on it. This was my first program, written in a language called BASIC:

10 CLS

20 PRINT "YOU'RE AN IDIOT"

30 GOTO 20I remember the infectious enthusiasm of a number of my teachers: my design and technology teacher, a gentleman called Eric Rose, showing me how to program a robot arm he'd made and the school librarian, Philip Wilson, encouraging me to explore and experiment with bulletin-board systems and a long-forgotten service called PRESTEL (forerunners of today's consumer internet).

I wouldn't be a programmer were it not for such positive formative experiences.

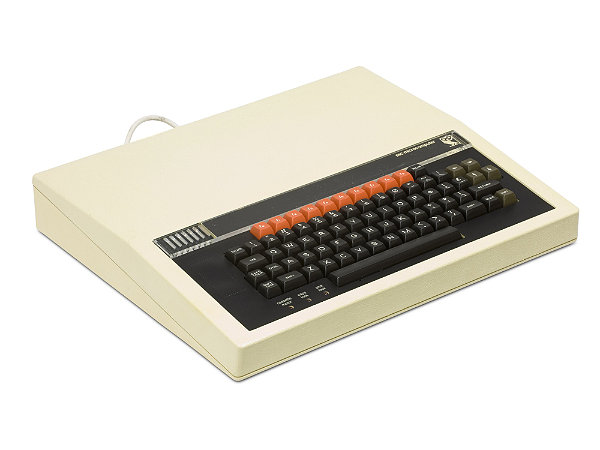

The computer I used was, of course, the BBC Micro: the result of an extraordinary initiative called the BBC Computer Literacy Project.

David Allen, the project's producer, explained that, "[t]he aim was to democratise computing. We didn't want people to be controlled by it, but to control it."

Fast forward to today.

Thanks to the efforts of teachers in organisations such as CAS and extraordinary world-changing projects like the RaspberryPi, computing education is undergoing a renaissance in the UK and the BBC are stepping up to help once more. The Python programming language is part of this effort and you can get involved.

What follows is the story so far...

In December 2014 the BBC announced their intention to create a mysterious computing-in-education project with "partners". I had recently organised PyCon UK's education track, people knew I was a Python Software Foundation (PSF) fellow and kept asking me if the PSF was involved. I decided to investigate and, with the blessing of the PSF board, applied for the PSF to join said partnership.

The BBC explained a staggering "moon-shot" project: to create a small, computing device to be delivered to ALL year 7 children (11-12 years old) in the UK. The newly christened BBC micro:bit would facilitate the first step towards inspiring digital creativity in a new generation of school children. I could identify with that!

At the beginning of 2015 a partnership was formed to deliver such a device and the PSF were on board to deliver educational support, resources and Python expertise. The BBC told us they already had a partner to create a Python "solution" for the device.

Over the spring I volunteered my time to attended meetings at the BBC and got to know several of our fellow partners: ARM and Tech Will Save Us were designing the hardware, Microsoft was to supply a child friendly development environment and many more were tackling other aspects of the project. I spent my time working out how to engage with our extensive network of Python-using teachers who could experiment with the device, create resources and train colleagues. I also wondered how to engage the wider Python community who, I was certain, would be very excited by the project.

However, I encountered two problems:

First, the project is covered by an NDA. The partnership agreement states that when the device is delivered all the resources needed to recreate the project are to be released under an open license ~ the laudable intention being an unencumbered legacy so others can build upon and adapt the work of the partnership. The NDA exists for the same reason there's a pre-broadcast NDA in place for the makers of Doctor Who: it avoids spoilers that would lessen the impact of the launch. Unfortunately, saying "NDA" to anyone from a free software background (such as Python) is a sure-fire way to turn them off (at best) or become hostile (at worst). This wouldn't be an easy sell!

Secondly, at the end of April I was asked to a meeting at the BBC where I was told the partner tasked to supply Python had dropped out. "We must have Python on the micro:bit" said the BBC. "I think you want the moon on a stick" I thought. Nevertheless, I agreed to look at Microsoft's TouchDevelop platform with a view to creating a version of Python to sit on top of the development environment and cloud based compilation service. I would need help, so asked those UK based Pythonistas I knew who had the right skill-set and interest in education to sign the NDA and help me evaluate what to do next.

Microsoft's TouchDevelop is a fascinating open source project: it's a browser based visual IDE for kids that generates a JSON based AST that's turned into C++ and sent to ARM's mBed cloud compilation service. Ultimately, a hex file is delivered to the user's browser and downloaded onto their local file-system. Plugging in the micro:bit makes it appear as USB storage and you flash it by dragging the hex file onto the device.

Python is, of course, a dynamic interpreted language rather than a static compiled language such as the one used by TouchDevelop. Furthermore, a version of Python that compiled to the TouchDevelop AST would be a completely new language - a Pythonic shim to make TouchDevelop feel like Python. Finally, TouchDevelop itself is written in TypeScript, an interesting Microsoft-developed language that compiles to JavaScript. None of us evaluating TouchDevelop knew TypeScript and the thought of creating a new compiler for a sort-of-Python, frankly, gave us the collywobbles.

Ultimately, designing and creating something Python-ish to work on TouchDevelop appeared to be impossibly difficult (or difficultly impossible, depending on how you looked at it) for a handful of volunteers working in their spare time in an unfamiliar language.

It was at this time that something amazing happened.

I was at a partner's meeting at the BBC and, quite by accident, struck up a tea-break conversation with "Jonny from ARM, pleased to meet you". It turned out that Jonny is a fellow geek, but one that inhabits a different layer of the computing stack (I generally work in high level languages like Python or JavaScript, Jonny feels more at home close to the bare metal hacking hardware).

After we'd figured out the above, Jonny asked, "have you ever heard of MicroPython?" (MicroPython is a full re-implementation of Python 3 for microcontrollers used in small devices such as the micro:bit).

"Why yes", I replied, "I've spoken to Damien several times over the phone since he was invited to speak at last year's PyCon UK" (Damien is the Cambridge based creator of MicroPython).

"Cool, I know Damien too, he's my next-door-neighbour", explained Jonny, after which he casually told me, "you know, it should be possible to get MicroPython to run on the micro:bit".

"Really..? The BBC had told me they'd looked into MicroPython but the device had the wrong chipset..."

"Oh, that was correct for the prototype. But we've changed the chipset. I'm pretty certain it'll work now."

Soon after I went to see Damien in Cambridge. I explained the project and he agreed he'd be willing to volunteer some time to explore porting MicroPython onto the device (Damien, like me, has a full time job). I organised for him to sign the NDA and Jonny supplied Damien with the appropriate things needed to compile MicroPython for the target chipset.

About a week later (at the very end of May) Damien emailed myself, Jonny and a few interested people at the BBC:

Thanks Jonny for the nRF mkit dev board, it has proved very useful!

I signed up to mbed, exported the blinky example for the mkit and got it compiling locally using a local toolchain. And then using this I managed to get MicroPython compiling and running on the mkit! There is a surprisingly large amount of room: I could enable floating point support, aribitrary precision integers, most of the Python features and a few builtin modules. The REPL works over the USB-UART with history and tab completion. It even has a working ctrl-C (meaning you can break out of an infinite loop). I implemented a basic "pyb" module with LED and Switch classes, and a delay function. So you can do something like:

led = pyb.LED(1)

while True:

led.toggle()

pyb.delay(100)

I'm not ashamed to say that I danced around the room fist-pumping the air shouting "woo hoo" when I read Damien's email. It confirmed there was a real possibility of getting proper Python to run directly on the device itself.

A week later I was in London for another partner's meeting where I was to get my hands on one of the very first batch of final-design devices. It was heartbreaking to be given such a cool device only to have to pass it to Jonny with the sad plea, "can you post this through Damien's letter box please?".

Over the next days Damien, Jonny and I kept in touch as Damien worked around some teething problems. Then, on the 17th June, Damien emailed again:

Using your new USB serial firmware and demo program I have now got MicroPython running on the micro:bit!

We finally had confirmation that MicroPython was going to work on the device! Much dancing, fist-pumping and shouts of "woo hoo" took place as I emailed the BBC with the good news.

They asked how we could integrate our work into TouchDevelop so I embarked upon writing a browser-based code editor (starting from the excellent ace editor). This is mostly done apart from some design tweaks. It's currently embedded in a test instance of TouchDevelop and works really well!

Interestingly, because this is Python we don't have to use the cloud compilation toolchain. Since hex files are a simple format we worked out a way of encoding Python scripts written in the editor in such a way that they can be inserted into the appropriate place in MicroPython's hex file. When the device starts up it discovers the embedded Python and the script is automatically run. Since the size of the MicroPython hex file is a lot less than say, the total size of the BBC's news frontpage, we embed the hex file within our HTML (it's in a hidden div) and do all the processing locally in the user's browser. It means the Python editor will work offline. We also have a non-TouchDevelop version to run from your local filesystem (so you don't need to be connected to the internet at all!).

Most importantly, it's possible to use the Python REPL via the USB connection. It means it's possible to "live code" the device by typing commands into a prompt, just like I used to do on my old BBC Micro. It's a wonderful mechanism for playful exploration and experimentation so kids and teachers get to see the results of their code running immediately on the device. Such a tight feedback loop is very useful and lots of fun!

More recently, we've implemented a microbit module to

access the device's hardware (a couple of buttons, an LED matrix, compass,

IO pins, accelerometer and so on). We also held a code sprint at

PyCon UK a few weeks ago and, after various bits of NDA related fun, we've been

able to add some wonderful new collaborators. We're pushing ahead on interesting

new capabilities such as game-related functionality, optimizations

so it's easy to create animations on the LED display and a music API: connect

a speaker via crocodile clips to the IO pins and listen to bleeps and

bloops.

The video below, created for a friend who blogs about "favourite modules", is a few weeks old but gives a flavour of our current status:

We also sent a micro:bit to Guido who appears to be quite chipper about the project:

I've been playing with micropython on the BBC micro:bit and it's amazing! <3

— Guido van Rossum (@gvanrossum) October 13, 2015

But there is still lots to do and we are a small team! The BBC understand the danger of a low bus factor (especially when work is being done by a small ad hoc band of community volunteers) and how important it is to engage with existing communities who are sympathetic with the cause of computing education.

As a result I'm immensely pleased that from today the BBC have agreed that we can continue our work in the open and outside the restrictions of the NDA. The micro:bit related parts of MicroPython have been released under the MIT license and can be found at this GitHub repository.

The browser based code editor will follow soon.

Please take a look, poke around and help. If you feel you can contribute I will try (no promises) to get you a device for development purposes - but I will need to be confident that you'll do work and push code.

You can contribute in other ways too: documentation needs writing and we want to generate educational resources for the device. Get in touch if this interests you! Alternatively, if you have an idea for a fun Python related project, tell us about it and I'll try (again, no promises) to get you a device for testing purposes.

Contributions are welcome without prejudice from anyone irrespective of age, gender, religion, race or sexuality. Good quality code, ideas and engagement with respect, humour and intelligence win every time.

Could you contribute something to a project that will touch the lives of 1 million children and create a legacy anyone can use?

:-)