Public Key Cryptography ~ Concise and Simple

(As with all "concise and simple" articles I assume no prior knowledge of the subject and keep the length to less than 1500 words.)

Sometimes people need privacy: intimate declarations of love, doctors discussing a patient, engineers developing a new top secret world changing product and journalists planning an exposé of government corruption are just a few scenarios where privacy is both a reasonable and legitimate requirement.

This need extends to our digital lives. For example, sensitive credit card information is privately shared to complete on-line purchases. Furthermore, you may be that lover, doctor, engineer or political journalist in need of private communication via the Internet. Maybe you simply don't like the idea of others reading your personal digital communications.

Public key cryptography is probably the most widespread solution to ensure privacy on-line. This article briefly explains what it is and how it works before concentrating on its uses.

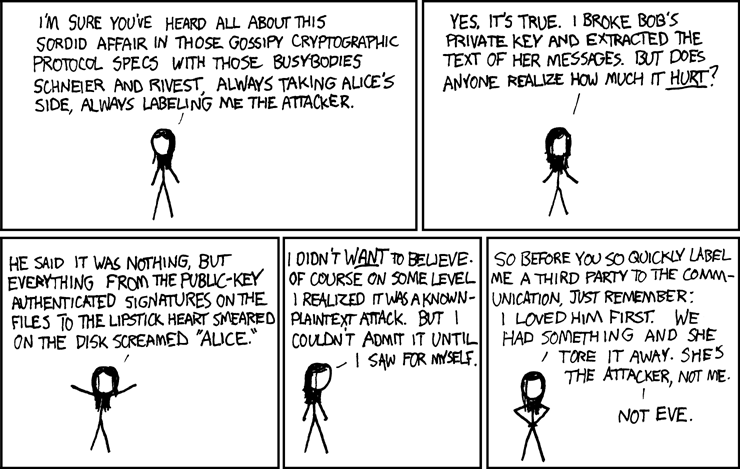

Cryptography is the study and application of techniques that secure communication in the presence of third parties (some of whom may wish to eavesdrop). It is traditional to identify the various parties involved in a cryptographic communication as Alice (the sender), Bob (the recipient) and Eve (the [sometimes nefarious] eavesdropper). In the specific case of communications sent via the Internet, messages may be handled by a large number of intermediary devices en-route to their destination. Any of these intermediaries may read the content of the message; in fact, they may need to in order to correctly route it to the intended recipient. To put it another way, the Internet is a public broadcast mechanism and its constituent devices are all Eve.

To overcome this problem, the meaningful content of messages (usually called the plaintext) is encrypted (in to something called the ciphertext) before being sent via the Internet. Such content appears as gobbledegook to devices handling the message on its journey to the recipient. Once received the recipient decrypts the ciphertext to retrieve the original meaningful plaintext message.

The process of encryption and decryption is done by a cipher - instructions that explain how to transform plaintext into ciphertext. An additional secret key, known only to the sender and recipients, is also used by the cipher to ensure only those with the key can read such communication.

Within a computing context the plaintext, ciphertext and key are all digital assets - things that are ultimately represented by binary values. In other words, such assets are merely very large numbers. Therefore, the cipher is only a mathematical function. It encrypts by using the key (a number) to turn the plaintext (a number) into the ciphertext (also a number). Decryption is similar in that it uses the key to turn the ciphertext into the original plaintext.

For cryptography to work both sender and receiver[s] must share information about the cipher and key to be used for secure communication. This presents a problem: how should Alice and Bob share such fundamental information? Any communication between them at this stage is insecure because they are yet to share and agree upon the cryptographic means for secure communication. Furthermore, Eve may be listening in to intercept such details and could use what she learns to listen in on the supposed secure communication. Alice and Bob find themselves in a crypto-chicken-and-egg situation.

This is where public key cryptography provides an elegant solution. Rather than use a single key, participants have two: a public key that they share with the whole world and a private key that they keep for themselves. Because of the mathematical relationship between the two keys it is only possible to decrypt a ciphertext with the other key in the pair. If Alice wants to send information to Bob she uses Bob's public key to encrypt her message and sends the resulting ciphertext. Importantly, only Bob can decrypt the message since only his private key can turn the ciphertext into plaintext. Eve can observe the complete exchange without gaining the information she needs to decrypt the message from Alice to Bob because Bob's private key is never transmitted.

Public key cryptography (specifically the

RSA algorithm) is

thought secure because it depends upon integer factorization - the process of

decomposing a number into its constituent prime-number divisors. In other

words, every whole number is the result of multiplying a unique set

of prime numbers together. For example, to get the number 12

use 2×2×3. As the number gets larger finding the constituent

prime numbers becomes too hard to be solved in a realistic amount of time.

Public key cryptography uses two huge prime numbers that result in

n, an even longer number whose length is measured in

"bits" (the longer the better) and whose value is used by the cipher.

Currently, n of 2048 bits length is considered secure

given currently available computing power (i.e. given a huge amount of

computing power it would still take an inordinate amount of time to crack).

In terms of the modus operandi of public key cryptography, that's about all you need to know without going in to technical details. There are many excellent explanations of how public key cryptography works "under to hood" and constraints of space stop me from going in to more detail. However, the video embedded below provides an engaging and comprehensive explanation and is part of the excellent series Gambling with Secrets by Art of the Problem.

An interesting side effect of public key cryptography is that it can be used to "sign" digital assets to prove provenance or identity. Given that any digital asset is simply a large number it is possible to use a hash function - a means of mapping variable length numbers to relatively small, fixed length numbers - to create a unique "signature" that can be cryptographically verified. Consider the following snippet of Python code (don't worry if you can't program, it's easy to follow):

from hashlib import sha1

my_digital_asset = open('war-and-peace.txt').read()

hash = sha1(my_digital_asset)

print int(hash.hexdigest().encode('hex'), 16)

This simply loads the complete text of

War and Peace

and uses a hashing

algorithm called SHA1 to

generate the hash that is printed on the screen as an

integer (whole number). The resulting hash for War and Peace is the number:

435515005527869578462696388723361351836071321997289162047109517397984640443675003720894549210723

Alice encodes this number with her private key and sends the resulting signature to Bob. Bob uses Alice's public key to decrypt the signature and retrieve the hash we generated above. Then he attempts to create his own hash of the complete text of War and Peace. If his hash matches Alice's he knows that both he and Alice are referencing the same digital asset. If the text for War and Peace had only one letter changed (either by mistake or because someone was tampering with it) then the hashes would have been different. As Bob knows only Alice has access to her private key, and only Alice's public key can decrypt such a signature then he can trust the provenance of the digital asset "signed" by Alice since only she could have created such a signature with her private key. In this way, Alice can also cryptographically sign her own messages to Bob.

It is important to acknowledge the political aspect of public key cryptography. Politicians, the Police and security services complain that terrorists and criminals use strong cryptography to hide their illegal activities. Laws such as the U.K.'s RIPA give the government and other public authorities (such as the Police or local council) powers to force you to hand over your private keys. When challenged about this curtailment of civil liberties (see article 12 of the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights) a common response is, "if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear". This is, of course, a dangerous attitude: the authorities get to decide what "nothing to hide" means and this changes all the time. For example, since the introduction of RIPA the list of authorities empowered by the act has increased four times (in 2003, 2005, 2006 and 2010). How would you feel if the recording industry became an authority and insisted you hand over keys so they can check your audio collection?

An Orwellian prospect if ever there was one.

Finally, development of such cryptographic technology is usually done in public by experts. It is open and public because problems and bugs are spotted quicker. Furthermore, designing and implementing cryptographic systems requires significant domain expertise. This convention ensures there are always freely available, well tested and well designed cryptographic libraries for non-expert programmers to re-use in their projects.

The challenge for programmers and cryptographers is to make the use of strong encryption the norm. It is ubiquitous for on-line financial transactions but most other things (email, web browsing, chat and other such digital interactions) are usually not secured. I suspect this will remain the case until people realise that their on-line life is currently like living in a house with no curtains.

Word count: 1439. Thanks to Terry Jones for typo spotting. Image attribution: © Randall Munroe licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC licence.