An Aesthetic Approach

Aesthetics (noun): The branch of philosophy that explores the nature of beauty, artistic taste and stylistic appreciation. Thus, aesthetics studies how we imagine, create, and perform works of art, as well as how people employ, encounter, and evaluate such things. Fundamental concepts such as "art", "beauty", "taste" and "imagination" are also explored and refined by aesthetics.

This article may only make sense to those for whom such thoughts are already familiar. That things don't make sense from a certain point of view is a core aspect of this article (viz. "brain twists").

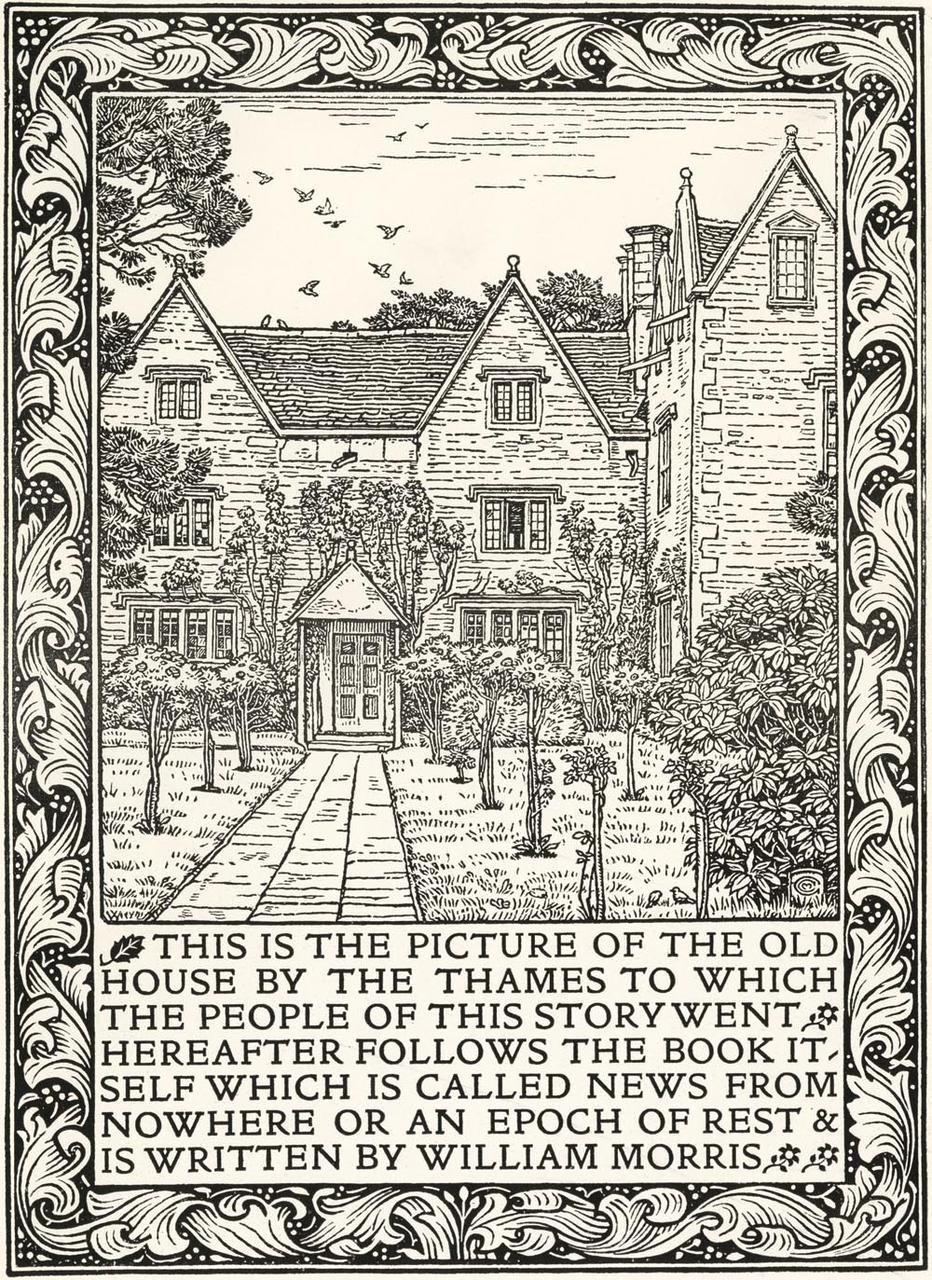

In the latter years of the 19th century the Arts and Crafts movement grew from the ideas and work of John Ruskin, William Morris and their collaborators. Rather than a particular artistic style, it was an approach to community organisation, an appreciation of the impulse behind artistic endeavours, and an attitude to the process of creating and making.

Work within this movement was diverse in style, execution and medium: it could encompass a colourful and richly decorated stained glass window, a simple rustic wooden table, medieval inspired typefaces, arboreal silverware, classical music inspired by English folksong or Renaissance composers, wallpaper patterns made from stylised tessellation of plants and animals, a red-brick neo-Gothic family home, and political, commercial or religious organisations with a vernacular, cooperative, emergent and egalitarian outlook.

© UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Source.

© Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum. Source (educational fair use).

© UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Source.

© Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum. Source (educational fair use).

by Ralph Vaughan Williams, performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

© UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Source.

© UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Source.

© UMD Special Collections and University Archives. Source.

© Gloucestershire Guild. Source.

Arts and Crafts was a reaction to the worst of the British Industrial Revolution: ornate and over-elaborate massed produced objects shoddily created via mechanised factories, ignorant of the qualities of the materials used nor the lives, skills and culture[s] of the workers involved. For the Arts and Crafts movement such objects, and the practices used to create them, had a detrimental effect on our world and the lives lived within it.

Arts and Crafts engaged with, and was an alternative perspective to, the complicated cultural and commercial status quo of its time. It emerged as an influential and widely admired movement that is still popular today.

What could we learn and recapture from the Arts and Crafts, as we reflect upon the equivalent knotty aspects of our own contemporary culture? It's plausible that shallow brand-led consumerism, unconscious automated manufacturing, efficiency obsessed supply chain practices and technology-enabled surveillance capitalism (that dominate our contemporary culture) are correspondingly damaging to the environment and our ability to lead flourishing and fulfilling lives.

For me, the alternative perspective of the Arts and Crafts resonates.

Why?

Because it's about paying attention.

How we pay attention reveals the world in a certain sort of way. Such attention changes the world through our actions embodying the subsequent understanding, interpretation and reaction to things from that certain perspective. Reflecting upon how one pays attention is, therefore, of fundamental importance. For such introspection cultivates a more enlarged and multifarious encounter with the world: an opportunity to become conscious of how one's own attention changes and is changed, while it is itself changing the world in which we live. Put succinctly, pay attention to paying attention!

In previous blog posts I've described this way of paying attention as a brain twist: the challenge to acquire a new perspective about seemingly everyday things. The external world remains as it was, but you have changed and thus see the world differently by paying attention with the benefit of a new perspective. It's that "aha" feeling when a cartoon lightbulb appears above your head.

Here's an aesthetic example of such a change of attention, from the perspective of the Arts and Crafts movement.

In a famous passage from Modern Painters, John Ruskin gave a celebrated definition of two types of beauty. The first, which he called "typical" beauty, is easy to understand because it is conventional. Typical beauty is the external quality of an object - how it may appear to us through our senses, "whether it occurs in a stone, flower, beast or man". The second, "vital" beauty, is where I find the brain twist. For it encompasses the, "felicitous fulfilment of function in living things" and the, "joyful and right exertion of perfect life". In other words, vital beauty relates to the quality of the expressive, moral and social effects of a work. As Ruskin put it, "the art of any country is the exponent of its social and political values".

In Modern Painters Ruskin defended the later paintings of J.M.W. Turner that were savaged by art critics of the time. Ruskin felt that to perfectly capture a scene with great accuracy (as one may naively suggest a photograph might do) is a fools' game because, "no good work whatever can be perfect, and the demand for perfection is always a sign of a misunderstanding of the ends of art". From Ruskin's perspective, this is because nothing can be completely seen, since the painter always creates via their own limited experience of the scene: from their unique (and thus incomplete) point of view. In the works of Turner Ruskin found an artist who expressed, through their paintings, a more fundamental way to pay attention to a scene. For Ruskin, Turner's focus was not how "real" or "accurate" the painting looked (the "typical") but how he, the painter, sees the more meaningful ("vital") aspects the scene. Such vital aspects are expressed through the skillful use of colour, contrasting light and shade, or brush techniques that subtly suggest, rather than accurately capture, the presence of things in the scene. Turner's genius is to give a more honest and truthful rendition of a scene as the artist sees it, although this actually makes the painting appear more unreal from a "typical" and thus incomplete point of view.

Public Domain. Source.

The "vital" aspects of Turner's The Slave Ship (shown above) encompass Turner's moral and political view of the scene - acknowledging the horrific events carried out by slavers, throwing overboard the dead and dying as a storm brews in the distance. Turner's work ensures the viewer has an opportunity to encounter and reflect upon such deeper and more meaningful aspects of the painting ~ above and beyond a superficially "accurate" rendition of the scene. I find myself first seeing a seascape with a dramatic sunset, then I notice the tall ship careering into a storm that looks like a demonic presence reaching into the painting from the left hand side. Finally I notice figures at the bottom of the scene in the foreground: a tangle of limbs and chains, into which I'm dismayed to discover are painted sea creatures and gulls feeding on those cast overboard. That I notice the human tragedy last of all is telling: Turner forces me to acknowledge my lack of awareness of the situation of slaves... followed by the self-realisation that such a lack of paying attention to slaves is perhaps a typical response from someone ignorantly encountering slavery.

It stops me in my tracks.

It is powerful stuff.

I am deeply moved.

Notice this depends upon my paying attention to the painting in a certain receptive manner (sympathetic to the "vital" beauty contained therein). Were I ignorant of Ruskin's brain-twist I may remark that the picture is just a messy and not especially convincing picture of a ship.

This is where the industrial revolution went wrong (from the point of view of Arts and Crafts): by focusing on the superficially typical beauty of mass manufactured objects at the expense of sharing and exploring works of vital beauty and depth.

Does this feel familiar?

Let's consider for a moment a corresponding view of the computerised world of the 21st century.

The typically beautiful looking social media app lacks the vital beauty of promoting a fulfilling and flourishing social life. Rather, it's a nefarious vehicle for shallow gossip and the delivery of (typically beautiful looking) adverts based upon invasive data collection. Your calorie counting app might help you measure your typical energy intake, but it isn't enlarging your awareness of the vitally delicious, healthy and skilfully prepared food you could be eating as part of a healthy lifestyle. It's actually a very specific and not particularly nourishing way of paying attention to the world (in fact, it's a tragically shallow and joyless exercise in data collection). The typically hi-tech coffee maker in your kitchen constantly reminds you of its presence via a glowing display that indicates the levels of coffee beans, water and limescale, and instantly gives you a cup of coffee at the touch of a button. How convenient? Alas, the vital and gentle ceremony of brewing coffee in a pot with the associated sensory and emotional stimulation it creates - the smell it produces, the relaxing aural experience of the bubbling sound or the opportunity to lovingly prepare a cup of coffee for someone else - is lost to a device that may look sleek and modern yet has all the lovability of a spare part for a Dalek.

The qualities of such artefacts reflect our way of paying attention to the world. As my examples demonstrate, at this moment in time our culture is often tragically obsessed with typical beauty and efficient convenience while ignoring or squashing latent vital beauty and the possibility for gentle and nourishing rituals or encounters with others. Furthermore, our culture has an unhealthy obsession with data and quantitative measurement as a means to "accurately" (typically) describe and pay attention to the world. To be clear, I'm not against data gathering nor quantitative measurement - these are demonstrably very useful and often essential for hoped-for outcomes and important informative analysis. The problem is with our attention: the tragically ignorant or inappropriate way to engage with and pay attention to the world in a relentlessly quantitative manner (we've measured it, so it must be true!). For instance, focusing on the number of "likes" on a social media post to indicate a meaningful social life, or counting calories as a proxy for healthy living, or coffee bean status as an important aspect of enjoying a drink with your loved one at breakfast.

Such misplacement of attention has an unfortunate side effect, a sort of self fulfilling aspect. By choosing to pay attention to things in a quantitative manner - a manner that gives an apparently clear "typical" answer - we get into a situation where anything that gives such an apparently clear answer becomes a priority. Why? Because we're able to quantify our quantitative outlook (we now have 173% more data points than last time, so it must be more accurate!). But in doing so we become blind to the vital process or quality of expressing other aspects of the world in more creative, intuitive, subtle or nuanced ways. The world is not black and white, nor even shades of grey, but full of colour, texture and subtlety (like a Turner painting).

Remember, it's not quantitative measurement that's at fault here (as I mentioned, that's often very useful!). Rather, it's our misplaced attention that's causing the problem. Such misplaced emphasis of attention inevitably leads to a crushingly banal and limited view of the world.

It's not fun. It's not rewarding. It's not even helpful.

In fact, it's probably dangerous because it ignores all the things that make life worth living: a fluid aesthetic process of encountering, understanding and expressing. Hence the importance of paying attention to "paying attention" to enlarge our encounters with the world and each other.

Here's another brain twist: my complaints are perennial, for every age is full of arty-farty humanist aesthetes (like me in this article) bemoaning the shallowness of their contemporary culture. Yet truth be told, if we only pay attention to the world in this more "vital" and aesthetic manner, we are just as incomplete and blind as those caught up in the "typical" or accurate view of the world.

Once again, the key is to pay attention to "paying attention". Ask yourself, is the sort of attention you bring to a situation the one that most completely reveals what's going on? Or perhaps trying several ways of paying attention is most beneficial to engaging with things? Maybe even a blended approach, to synthesise different ways of paying attention into a more subtle, nuanced and enlarged view, is possible?

The Arts and Crafts movement realised this and deliberately emphasised the integration of "vital" elements into typically "typical" aspects of their commercial endeavours. For example, William Morris encouraged useful work over useless toil and emphasised meaning and respect when collaborating. Their approach often favoured synthesis of vernacular traditions over a reductionist analysis of "products", in the belief that a work thus created would cherish and honestly reflect the qualities of the dynamic living culture in which it originated. For Morris, one should be fulfilled by such work, created within a recognisable (and thus authentic) shared cultural tradition, rather than crushed or alienated by artefacts, designed by committee, based on "data" and manufactured via automated production processes. Such work was to emerge from the bottom up - from those crafting the work - rather than through a managed top down technocratic structure. For the Arts and Crafts practitioner, their (typical) technique enabled (vital) expression rather than merely being a means of production. Importantly, such work took place in the context of guilds and privately owned companies (such as Morris's own Morris & Co.) which involved the "typical" bureaucracy of running a commercial enterprise or cooperative, all the while paying attention to the "vital" work of creation and collaboration.

This emphasis on the vernacular and organic "folk" traditions meant paying attention like Janus, both backwards and forwards in time, to the culture in which one was creating. Morris was inspired by the work of medieval artisans, their system of guilds and the way their work existed within traditions of practice, style and organisation. Morris also wrote utopian science fiction, such as his novel News from Nowhere that imagined a future agrarian society based on common ownership, democratic government and progressive cultural ideals fashionable at the time among his compatriots in the Socialist League.

The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.

~ William Morris

Paying attention to paying attention enables us to mix, contrast and integrate different ways to encounter the flow and change of our world. Such diverse and multifarious encounters lead to a richer, enlarged and deeper understanding of the universe. Ultimately, we cultivate a bountiful repertoire of disparate and resonant material, skills and experiences upon which we draw as we react to our world by expressing ourselves with creative and collaborative endeavours.

As artists and crafts-folk (meant in the broadest sense) mature and refine their technique their wisdom, gained by paying attention to the experience of living in a complex and ever changing world, is found in the fruits of creative work. Their presence, embodied through such works, makes available their acquired and unique perspective to those willing to engage, pay attention, and mature.

Cultivating those vital aspects of the external world that grow and nourish oneself from within is the work of a lifetime. Our current culture, of problems to be fixed, arbitrary achievements to unlock and self-worth expressed as a measurable external quantity (typically money, number of cars, size of home etc) is the antithesis of this most important work. For our self-esteem, if expressed in terms of possessions, will always be unrequited.

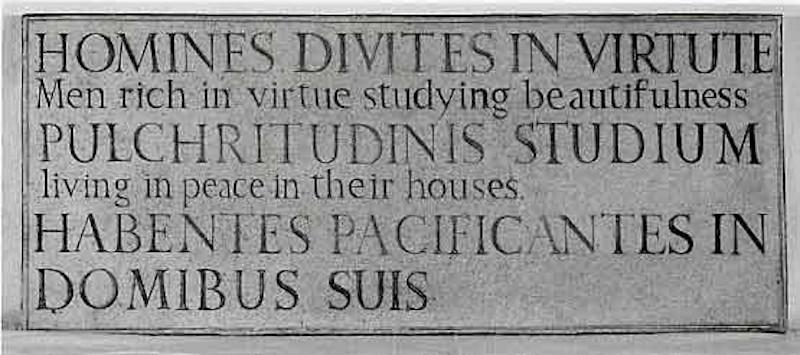

There is no wealth but life. Life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration. That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest numbers of noble and happy human beings; that man is richest, who, having perfected the functions of his own life to the utmost, has also the widest helpful influence, both personal, and by means of his possessions, over the lives of others.

~ John Ruskin