Movements of Thought

Why Computers Work (part 2)

(Part 1, part 3, part 4, part 5)

Just as one can describe rules for a card game, it is possible to describe rules for thinking: rules for movement of thought.

This is the study of Logic, and using these rules is called reasoning. Reasoning with logical rules allows others, who know such rules, to follow the movements of thought that brought you to a certain conclusion. Furthermore, because there are rules, it's possible to notice when they're ignored or used incorrectly (when movements of thought don't make logical sense).

There are many types of logic, but the one we're going to examine is called propositional (or sentential, or boolean) logic.

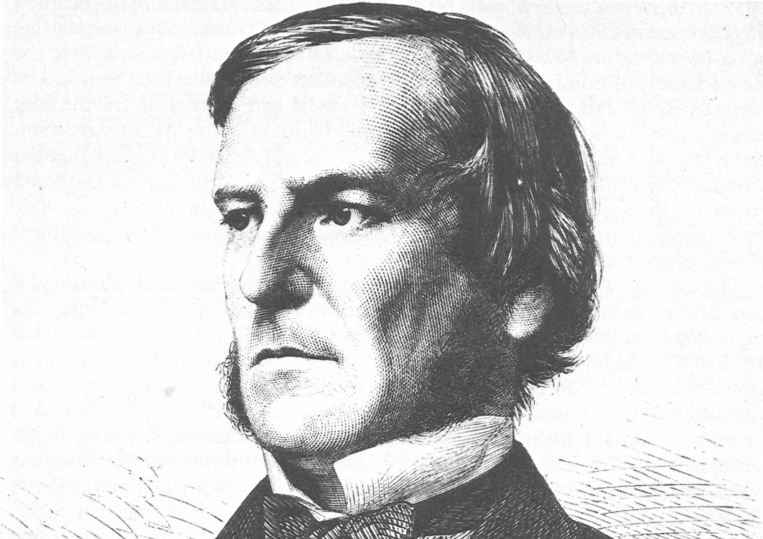

"Propositional" and "sentential" are just descriptive names for a type of logic that deals with forming sentences by combining propositions. In logic, propositions make assertions that are either true or false. George Boole (1815-1864), shown below, invented a system of mathematical algebra that works like propositional logic (it also deals with values that are either true or false) and so the term "boolean" is often used synonymously.

Here's a contrived example of a sentence in propositional logic:

"If it is sunny and I am wearing a thick coat, then I am hot."

I want to draw your attention to some important aspects of this sentence that may not, at first, appear obvious:

- It contains two propositions called premises ("it is sunny" and "I am wearing a thick coat"). Premises make assertions about states of affairs.

- It ends with a conclusion ("I am hot"). A conclusion is a proposition that depends upon the premises in some way.

- The sentence is in the form of a conditional ("if [premises], then [conclusion]"). A conditional is a rule saying that if its premises are true then the conclusion must be true.

- The premises are related to each other by a logical operator called a conjunction ("and"). This is another rule: if the related premises are evaluated together, collectively they are true only if all of them are true.

Propositional logic describes the rules of a "game" to construct sentences that make logical sense. Playing by the rules of logic forces everyone to reach the same inevitable conclusion: if we accept that the premises are true (it is sunny and I am wearing a coat) propositional logic dictates the conclusion must be true (I am hot). The object of propositional logic is to use the rules to evaluate (work out) if a sentence is true or false.

Here's the brain twist: propositional logic doesn't care about meaning. The important logical aspects of the example above don't concern my state in the real world (which is why the sentence sounds slightly odd). Propositional logic only cares about truth and how propositions fit together. I could revise the example to:

"If A and B then C."

It doesn't matter what A, B or C stand for nor what they may mean -- from the perspective of propositional logic all that matters is there are two conjuncted premises (A and B) and a conclusion (C) expressed in a conditional (if ... then ...). If one or both of the premises is false, then the conclusion must also be false. Why? Because the logical rules pertaining to conditionals and conjunctions (and nothing else outside those rules) make it that way!

The brain twist is divorcing yourself from meaning -- just concern yourself with truth values of the propositions, the structure of the sentence and following the rules.

In the same way the rules of Snap explain what must happen, given card related states of affairs, so the rules of propositional logic do the same with propositions and sentences. The rules of Snap don't care what the specific values of cards are, just that such values may match. Similarly, propositional logic doesn't care what the specific meanings of the propositions may be, only that such propositions connect in a sentence that can be evaluated with rules dealing in just two possible states: true and false.

The simplest way to express the rules that govern such logical operations for connecting propositions is with a truth table.

Here's the definition of "and" (conjunction):

A | B | A and B ---------------- F | F | F F | T | F T | F | F T | T | T

Can you see how it works?

The first two columns represent propositions labelled "A" and "B". The third column represents the outcome of the "and" operation, given the values of "A" and "B" in the first two columns. Each possible combination of truth value for "A" and "B" is enumerated as a row with the resulting truth value for the "and" operation in the third column. It's a simple tabular way to express the rules of propositional logic. If you had any doubt how "and" (conjunction) worked, you'd find the definitive answer in this truth table.

For instance, take the first row: if propositions "A" and "B" are both false (as expressed in the first two columns), then the outcome for this rule (expressed in the third column) must be false.

Here's another truth table that defines the rule for the logical operation called "or" (disjunction):

A | B | A or B --------------- F | F | F F | T | T T | F | T T | T | T

Let's pretend that "A" is false but "B" is true. How would you evaluate the truth value of "A or B"? Is it true or false?

The answer is that "A or B" is true. Why? Because the second row tells us so: the "A" column is false, the "B" column is true so the result, expressed in the third column, is true.

Here's one final truth table. It's a bit different to the other two since it only works on a single proposition:

A | not A ---------- T | F F | T

It's easy to see what the "not" (negation) operation does to a proposition: it flips its truth value so false becomes true, and true becomes false.

While these logical operations have familiar names ("and", "or" and "not") that appear to relate to how they work, it is the truth table and only the truth table that defines how they behave in propositional logic, not any similarity to how we may use such words in everyday English. There are further rules, expressed as truth tables, for connecting propositions that you may wish to look into. They are XOR (eXclusive OR), NAND (Not AND), NOR (Not OR) and XNOR (eXclusive Not OR).

Logical puzzles become fun when you combine such logical operations to build more complicated structures. Take for example:

(A and B) or (C or not D)

I've put parentheses ("(" and ")") around propositions so you can see how they

relate to the logical operators (the and, or and not). If we pretend all

the propositions represented by letters are false, what is the overall truth

value of the sentence?

To find the answer we play the logical "game" in the same way we would with Snap: we follow the rules.

Start by evaluating the operators within the parentheses. If we replace the propositions "A" and "B" with their truth values (remember, all the propositions are false), we get:

(false and false) or (C or not D)

Given the rule set out in the truth table for "and", the propositions in the first parentheses evaluate to false. Here's how the sentence looks as a result:

false or (C or not D)

To evaluate the "or" in the remaining parentheses we should first evaluate the "not" operator to find the truth value of the proposition on the right. If "D" is false, then the truth table for "not" tells us that "not D" must evaluate to true. Since "C" is false, the sentence looks like this when "C" and "not D" are replaced by their truth values:

false or (false or true)

The truth table for "or", when applied to values in the remaining parentheses tells us that if one of the propositions is true, then the "or" operation must evaluate to true, giving us:

false or true

Re-using this rule to evaluate the remaining "or" operation gives the result:

true

The only way to solve such logical puzzles is by following the inevitable steps dictated by the rules. That's how logic works!

But why does logic work?

For the same reason why the game of Snap works: we modify our behaviour to follow unambiguous rules because we want to determine the truth of sentences in propositional logic (the aim of playing this sort of logic game). Furthermore, by pretending propositions represent states of affairs in the real world, we can use logic to describe and, in a sense, encode aspects of the real world. For instance, we could describe the rules of Snap with logic.

But why is logic useful?

Because logic clearly and unambiguously describes the relationships between

states of affairs (premises), and allows us to take action given a resulting

truth value. Consider, for example, this conditional statement: IF the card

on top of stack A is an ace AND the card on top of stack B is an ace, THEN

shout "SNAP!". Logic describes the movement of thought needed to participate in

the card game (or any other useful structured activity).

Here's a final "brain twist" for you:

If Logic provides an inevitable, almost mechanical framework for organising and describing movements of thought then we should be able to build machines to work with such seemingly mechanical logical rules.

It turns out that we can, and describing such machines is the next step in describing why computers work!