Counterpoint, "In C" and Code

I recently found some old teaching materials I used to use for an adult-education class in beginners musical theory. It was targeted at interested non-musicians so everything was simply defined with concise examples. I'd forgotten I'd written my own musical fragments for explaining counterpoint and was pleasantly surprised at what I'd produced (inevitably in the style of J.S.Bach). Yesterday I had reason to use the free music typesetting programme Lilypond for the first time in five years. I was having so much fun that I decided to input my old examples into Lilypond and here are the results (with appropriate commentary):

Counterpoint…

...is the pleasing combination of two (or more) different melodies, often of contrasting nature (for example, melodic shape or rhythmic texture). The first melody to be introduced is called the "Subject" with additional melodies being called "Counter Subjects" (often numbered 1..n if there are more than one).

Here are two melodies:

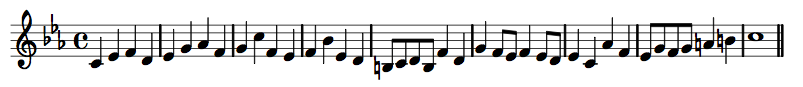

Subject

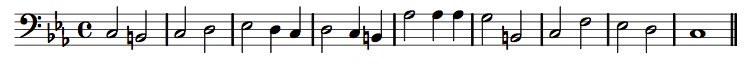

Counter Subject

Notice how they differ from each other: the "Subject" usually moves by leaps and contains many quaver notes making it sound very "busy" whereas the Counter Subject usually moves by step and has an altogether less urgent rhythmic feel to it (lots of minims). Notice also that the shapes of the melodies are similar in the first four bars (a general rise then fall) and contrary in the final bars.

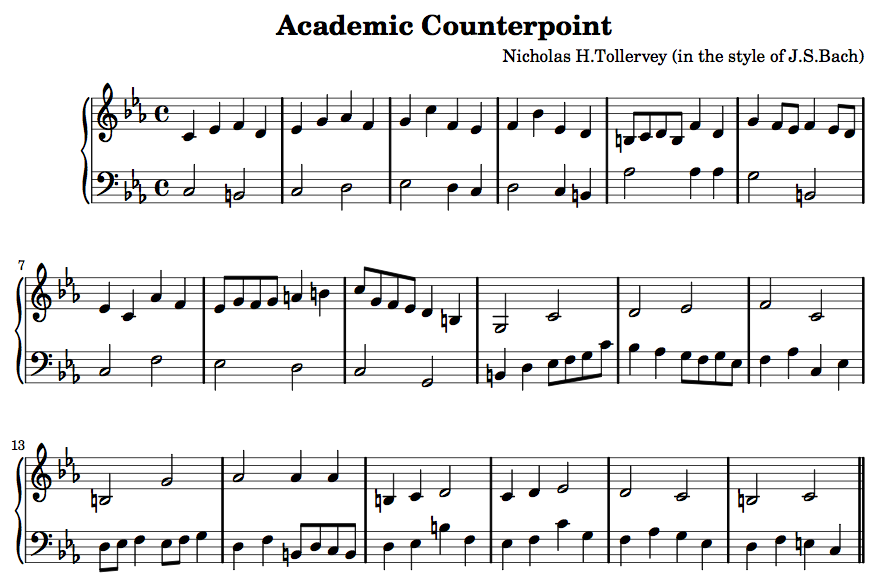

It is these differences between the melodies that make the resulting counterpoint interesting to listen to:

Combined Melodies

This is all very clever and hopefully sounds good, but there is more! In contrapuntal musical forms such as the Fugue once the melodies have been introduced the composer will often "develop" the material in cunning and surprising ways. Below is a rather incomplete list of melodic transformations one might employ to keep the listener on their toes (you need to know what you're listening for – but it can turn into quite a good game):

- Inversion – the original melody is turned upside down. Where the pitch moves up by three notes in the original, it moves down by three notes in the inversion.

- Retrograde – the melody is played backwards.

- Augmentation – the duration of the notes in the original melody is lengthened by a constant amount (for example, all note lengths are doubled).

- Diminution – the opposite of augmentation, the notes are shortened by a constant amount.

Obviously, these tricks can be combined to get transformations such as retrograde-inversion (backwards and upside-down) or augmented-retrograde (lengthened and backwards), for example.

Composers will then start to combine these combinations so you might end up with the subject being played in counterpoint to itself as a retrograde-inversion above a third part that is an augmentation of the counter subject. Fantastic stuff!

To illustrate this point, here is our original contrapuntal example followed by itself in retrograde with the parts swapped between bass and treble (making it a musical palindrome):

With Retrograde

Notice how I make sure the melodies conform to the melodic-minor and introduce a Tierce de Picardie at the end so some of the notes are not exactly the same in either direction.

"In C"

Fast forward to yesterday. I recently discovered a great musical experiment on YouTube called: In Bb

As you'll see when you click the link, you are presented with YouTube clips of performers playing improvised fragments in the key of B flat major. As the visitor to the site you create the "counterpoint" by starting, pausing and stopping the videos in a sequence of your choosing. You may even "mix" them – to a limited extent – by changing the volumes associated with each video.

Although not the formal "classical" counterpoint I describe above, this is definitely the pleasing combination of two (or more) contrasting melodies. I was very impressed.

After mentioning this on Twitter I was helpfully reminded that it was similar to Terry Riley's In C (the second link is to the score). I was a big fan of this piece when I was at music college and it explained why "In Bb" sounded so familiar.

In C is an aleatorical composition (i.e. it includes elements of chance in its performance) and consists of fifty-three short musical "subjects" to be performed repeatedly an arbitrary number of times but in sequence. Riley suggests that musicians keep within two-three fragments of each other.

Once again, this isn't the formal "classical" counterpoint I described above, but it is the combination of thematic subjects into what has been described as the world's first minimalist piece.

I've found several performances on the Internet: this one is a midi realisation whereas the following excerpt from a live concert is performed by a symphony orchestra.

Code

This brings me onto my current vocation (software developer)...

You can't have failed to notice that what makes counterpoint (and music in general) interesting is the introduction of melodies (fragments, subjects or whatever) and their combination and transformation through time. If I replaced the word "melody" with "data structure" in the preceding sentence then you have a pretty close analogy to how software works.

Like any analogy, I accept that it isn't a completely "sane" mapping from one world to the other, but I can't help but want to be able to compose music in code. Something along the lines of this (in Python):

subject = melody([ c(4), c(4), g(4), g(4), a(4), a(4), g(2)])

subject.rhythm()

[4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 2] # 6 crotchets followed by a minim

subject.pitch()

[c, c, g, g, a, a, g]

subject.intervals[ 0, 7, 0, 2, 0, -2 ] # intervals between the notes in semi-tones

subject.invert()

[ g, a, a, g, g, c, c ]

Obviously, I'd need to work out the API in a lot more detail – the above example is just from the top of my head – but I think it'd be great fun to implement something like this.

Hang on… what's this..? :-)