CERN

Last week I visited CERN with my youngest (16yo) son, William.

Our road to CERN started in the summer at EuroPython. Will volunteered at the conference registration desk and checked in Phil Elson. Noticing Phil's conference badge (indicating he worked at CERN), physics-mad Will started asking Phil all sorts of questions.

Further physics conversations ensued between Will and (the ever patient) Phil over the course of the conference. In the end Phil suggested we just come visit CERN and Will could explore to his heart's content. Furthermore, since I had presented a talk about PyScript at the conference, Phil mentioned colleagues at CERN who'd be interested in learning more about the project and who may possibly have uses for the work I'm currently doing. A plan was hatched for a "dad and son" adventure to CERN so Will could soak up the physics and I could present and meet with fellow coders.

Thank you to Phil, Jo and their children for putting us up during our visit to CERN. Staying at chez Elson was, in itself, worth the trip. Both Will and I had lots of fun with the Elson children, be that reading stories together or helping with dressing up.

The photograph of the "#I💙CERN" sign, at the beginning of this post, was taken outside the brand new education centre on the day we arrived at CERN.

As a former teacher, and someone still passionate about engineering education and pedagogy, this brand new facility was great fun to explore. The curators have put together an excellent set of displays, videos and interactive props along with a comprehensive timetable of lectures, classes and workshops.

This is how to engage folks with science, technology and engineering. Bravo!

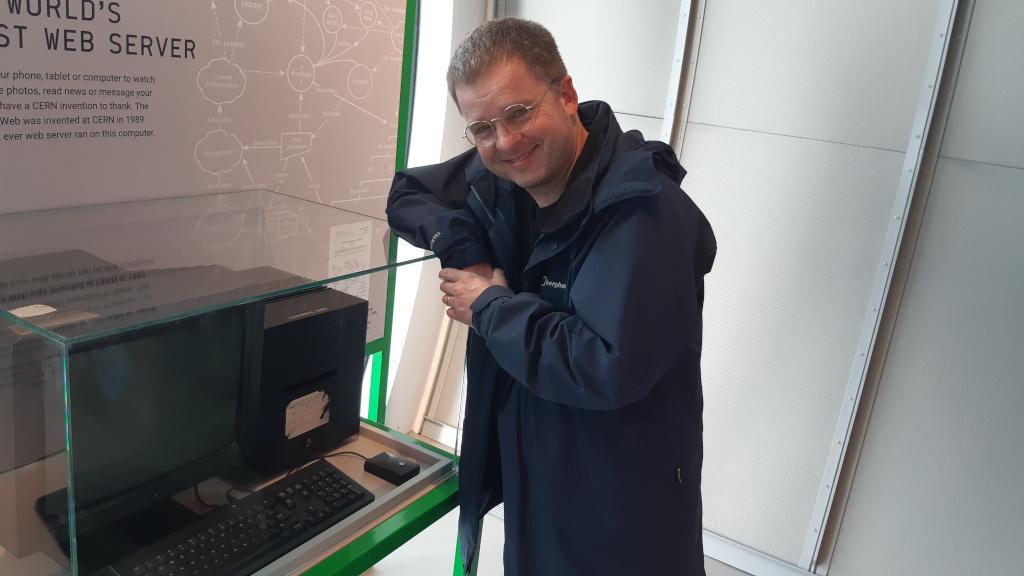

Tim Berners-Lee worked at CERN when he invented the World Wide Web (through which you are reading this blog post). I was delighted to find a small display in the exhibition space explaining his work and the origin story of the web, along with the computer used to develop the very first web server.

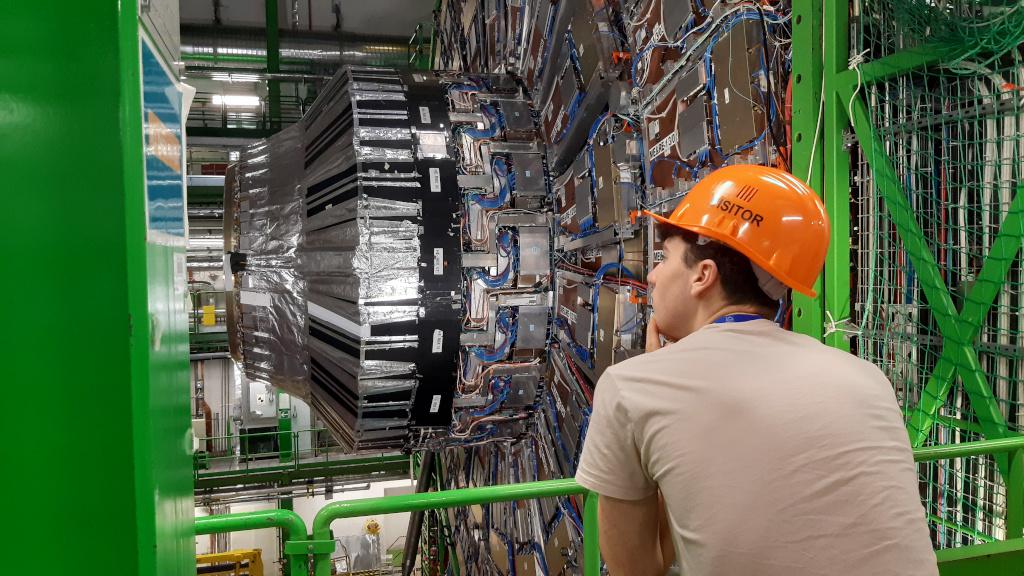

The next day started at 8am with a visit to the ATLAS detector. The CERN facilities were off for maintenance and upgrades, so we were able to get to places not normally open to visitors like us.

The Large Hadron Collider is the world's largest and most powerful particle collider. It is 27 kilometres in circumference and buried around 100 metres below the French and Swiss countryside. Put very simply, its job is to smash protons together so physicists can analyse the resulting subatomic particle "debris" and learn more about the structure of the subatomic world and the laws governing it.

The collisions happen at several points in the LHC and it is at such points that particle detectors, like ATLAS, are found.

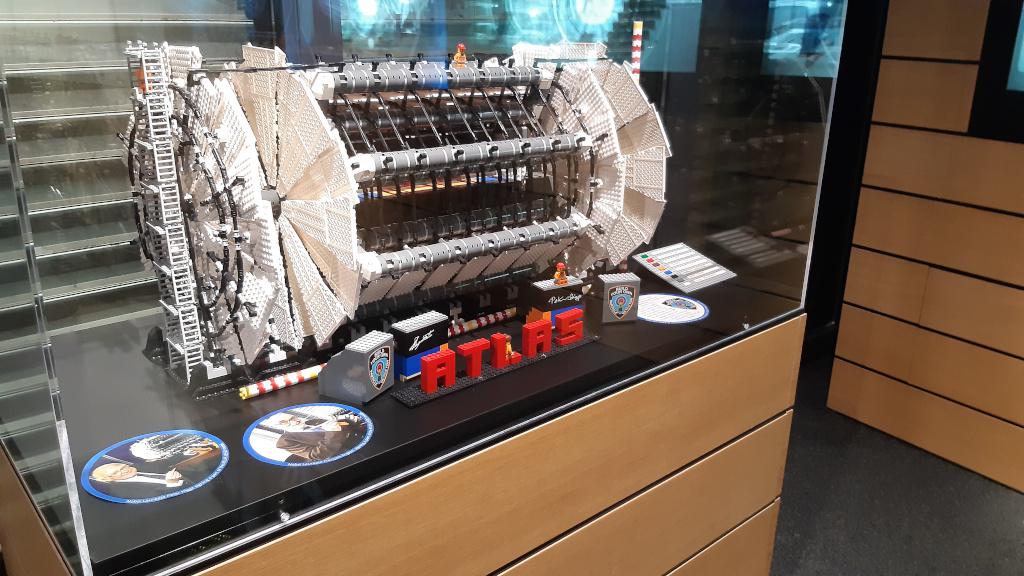

This being the first visit of the day to CERN facilities, the journey to the device left quite a theatrical impression. We had to don hard hats (making us all look like the Lego mini-figures on the model in the reception area), watch as our guide used a retina scanner to access the facility (very Hollywood), and travel 100 meters below the surface in a lift. We emerged into a labyrinth of tunnels adjacent to rooms containing racks of computers and other equipment needed to run the experiment.

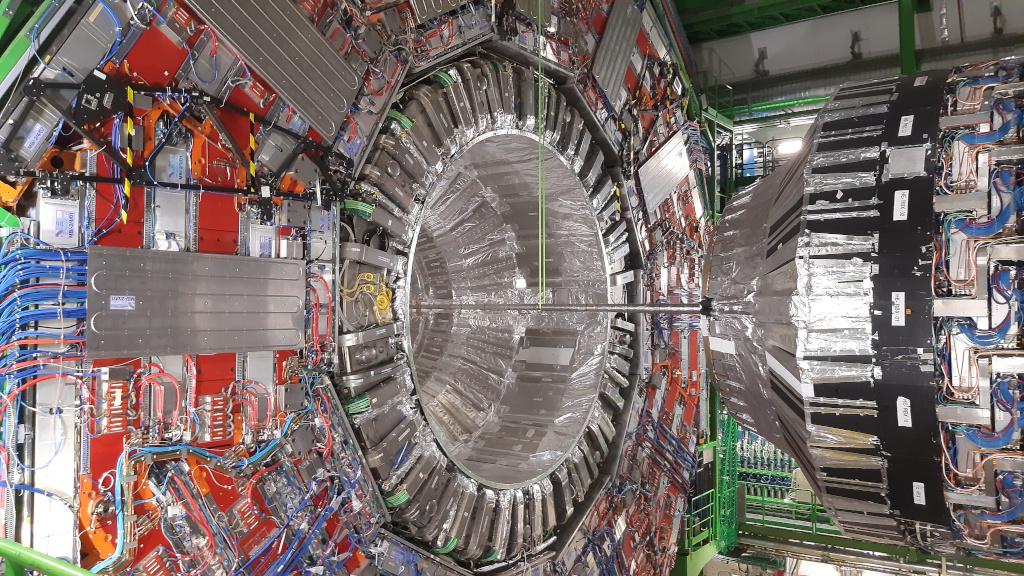

Finally we got to the cavern containing ATLAS.

Photos of ATLAS don't do it justice: it is so overwhelmingly HUGE that your whole field of vision is filled with the device (it is seven stories tall). Imagine constructing a large multi-story car park filled to the brim with intricate electronics, in a ship-in-a-bottle manner but 100 metres underground. What a feat of planning, engineering and construction!

ATLAS is made up of layers, each of which detects different sorts of subatomic particles - hence the circular arrangement of equipment centred on the particle beam.

Each collision creates terabytes of data, most of which is processed as close to the device as possible and thrown away. Only those aspects of the data that are of interest get to make it to the data centres on the surface and then to a global network of computers crunching and analysing the results (the World Wide Web was invented specifically so scientists could share such data).

Once the mind boggling scale of the device had been processed, as well as its extraordinary engineering explained, William took the opportunity to ask the physicists on hand all the questions about all the things. I have to admit, I had no idea what they were talking about... I am a classically trained musician with a background in academic philosophy who earns a living as a software engineer, and so their conversation was well beyond my level of subject matter knowledge.

Here's the thing, not for the first time I observed folks recognise in Will a fellow physics enthusiast. Then they would open up about their passion for their work and scientific interests. This was a privilege and joy to behold, and Will was in his element. He really appreciated their time and patience.

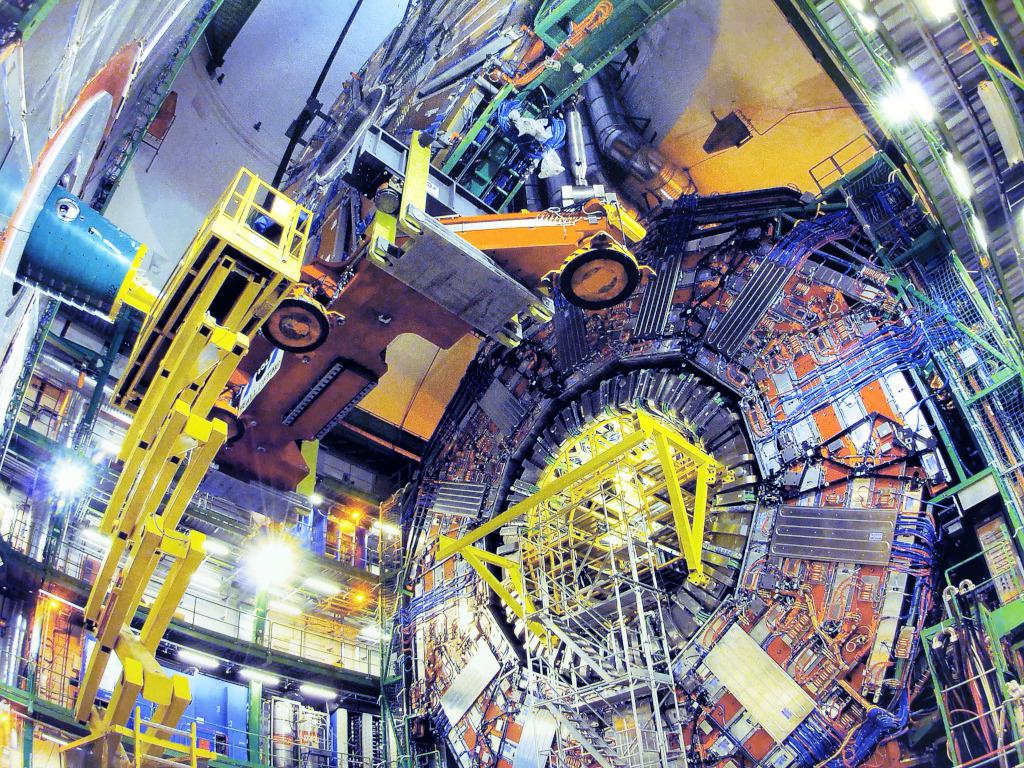

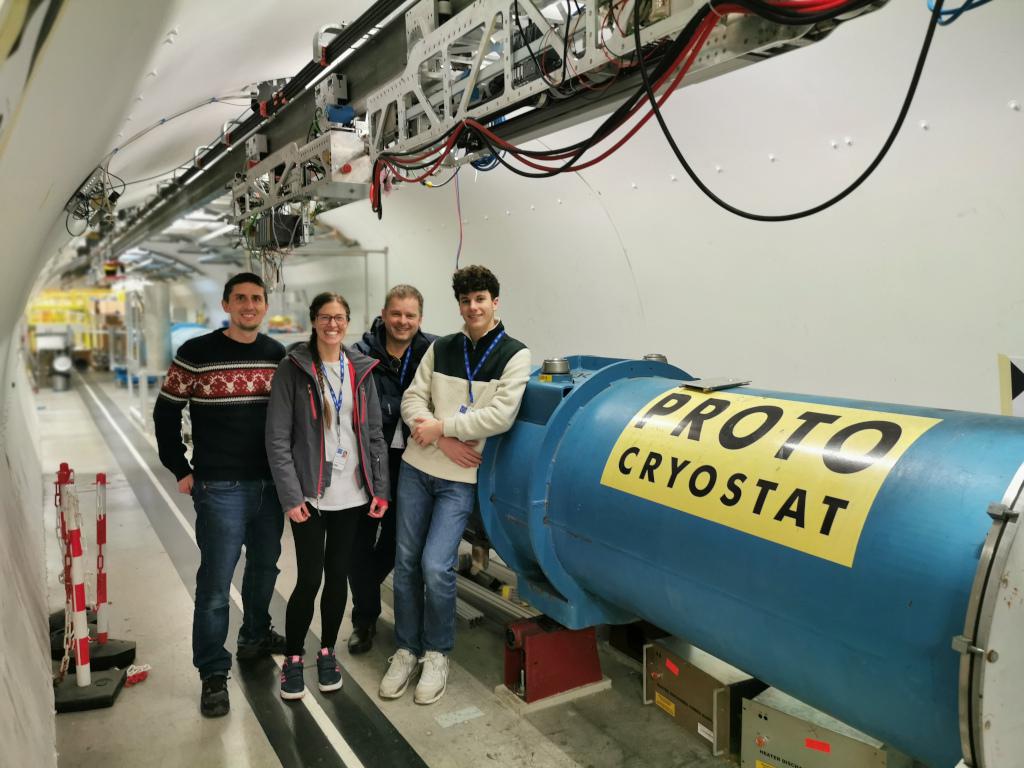

Between technical meetings in the morning and a presentation about PyScript in the afternoon, we saw many other parts of the CERN facilities. The highlight for me being a visit to CMS, another titanic machine and feat of engineering 100 meters below the surface.

The CMS device is, like ATLAS, a sub-atomic particle detector but at the antipode of the LHC to ATLAS.

As I understand it, CMS and ATLAS essentially do the same thing but were designed by independent teams so the resulting devices differ in their capabilities and the details of their engineering. They complement each other because the results from one device check and confirm the results of the other, thus giving scientists greater confidence in the data coming from the detected collisions in each device.

There is, of course, a friendly rivalry between the two teams and I quipped to our CMS guide, Benjamin, that it felt like CMS and ATLAS are to physicists as vi and EMACS are to computer programmers. To which Benjamin shot back, "I'm a vi user". This was yet another hint at the renaissance man/woman aspects of many of the hugely talented folks working at CERN. Through the course of our tour, not only did Benjamin reveal his background in Physics (by fielding yet more questions from Will, of increasing incomprehensibility to me) but touched upon the various engineering aspects of the CMS device as well as sojourns into materials science, computing hardware and "big data". Bravo Benjamin, this was an entertaining virtuoso performance of passion for the project.

Once again, the scale of the device was overwhelming.

The service tunnels and shafts underground were perhaps more accessible to see at CMS than at ATLAS, and these additional aspects of the life of the project gave yet another dimension of the overwhelming scale of what goes on at CERN. We were, in a sense, able to see the neck of the bottle through which the 14000 tonne CMS "ship" had been built.

It is while in the presence of such devices that one ponders how such things are maintained and improved, who designs them, and what resources are needed to make things work. It is then that one realises that CERN isn't just about science, it's also a sort of creative cultural experiment consisting of a huge number of people spread all over the world, collaborating to help us comprehend what the universe is and how the universe behaves.

However, such activity doesn't just happen at the titanic scale of ATLAS and CMS.

The protons that are accelerated and smashed together have to come from somewhere, and while visiting another CERN facility we found the source: a red bottle containing hydrogen.

If that looks like a thermos flask containing a nice hot cup of tea (hat tip), you're not wrong. Such mundane looking yet essential objects were another aspect of CERN that reminded me that any large engineering effort contains an abundance of seemingly boring yet rather important bits and bobs randomly attached to other stuff.

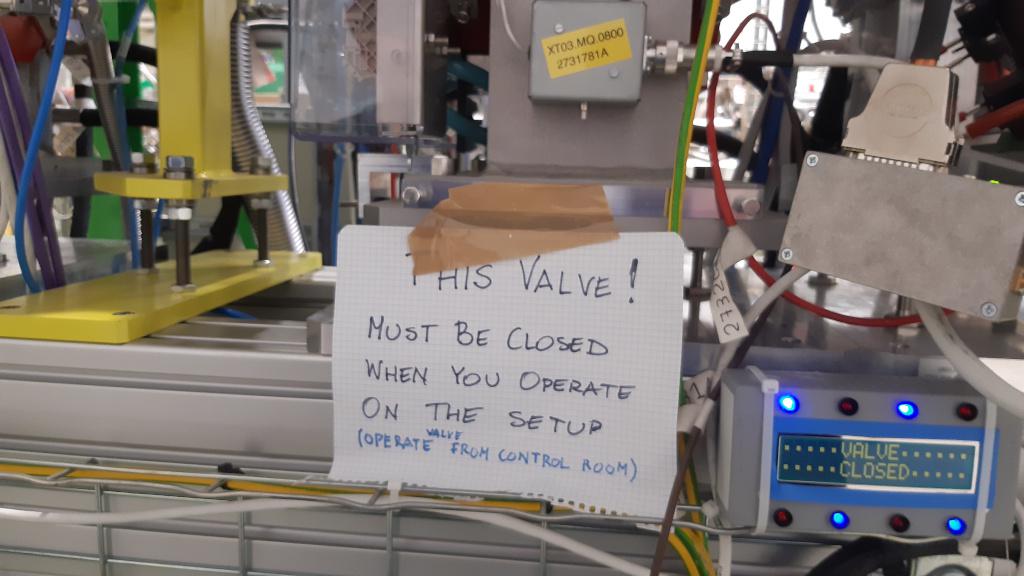

Another aspect of any complicated engineering effort is the inevitable use of hand written warnings hastily taped to a button, panel or (in the following case) valve:

In a similar vein, the LHC needs an "off" switch - a delightfully understated device found on the desk of an operator in the LHC control room. This is used when things don't go to plan.

When pressed the LHC isn't actually switched off... rather a dump of the beam occurs, where the protons, travelling at near the speed of light, get redirected in a spiral fashion to around 30 meters of material that act as a cushion to absorb the beam (to spectacularly over-simplify what really goes on).

CERN also has a sense of humour.

When I asked a guide what went on at a rather nondescript area on a schematic map of CERN labelled "north facility", they replied, with a twinkle in their eye, that it was where they manufactured all the black holes. Another scientist pointed at a door and exclaimed with glee that it was where they keep all the secret alien technology (but they'd have to kill me if they told me more).

Clearly such tomfoolery is a complete nightmare for CERN's PR and media department.

Thanks to the World Wide Web, not only can theoretical physicists share information, but conspiracy theorists can share their own unhinged, one-sandwich-short-of-a-picnic misinformation about what the universe is and how the universe behaves. This includes many Men In Black style assertions about CERN ~ such as the possible manufacture of world-ending black holes.

Rest assured, the most dodgy things I observed at CERN were an interesting looking risotto in restaurant 1, a desire to number buildings in chronological order of construction (something with which even Postman Pat would struggle), and a large number of champaign bottles in the CERN control room (clearly these folks know how to party).

Actually, if you look carefully at the bottles you'll notice that each is labelled with the name of a successfully completed experiment. Apparently it is traditional to send an appropriately decorated bottle of bubbly to the CERN operations team as a token of thanks for their considerable expertise and work running the LHC.

That there is a CERN operations team, whose job it is to "drive" the LHC for everyone else, is a reminder that CERN is not just full of physicists. There is so much complementary work going on. Remember, the reason I was at CERN was to talk about PyScript: CERN makes use of, and are interested in, all sorts of computing technology, a huge variety of engineering, and ever more creative ways in which to explain and share what on earth is going on to the rest of the world.

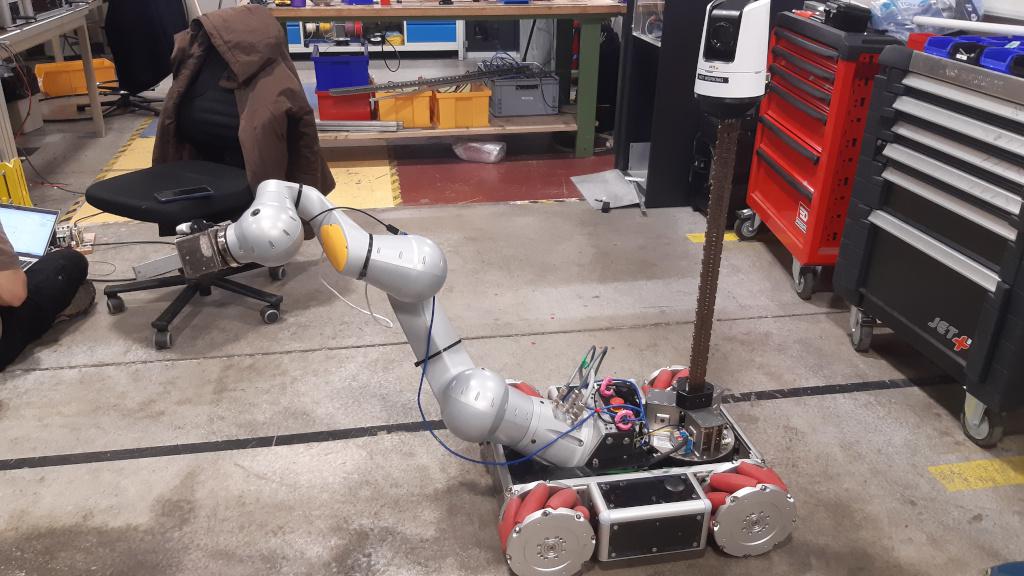

A wonderful example of such a complementary discipline at work at CERN was demonstrated during our visit to the robotics facility.

How do you service the LHC when it is functioning?

You don't send people down there!

Instead, you use robots!

This was our final visit at CERN, on the morning of our return home. What should have been a 45 minute quick guided tour extended to about an hour and a half of enthusiastic explanation and demonstration.

The robotics lab have mock-ups of all the different sorts of area at CERN in which the robots work, so they are able to test them and rehearse "situations". The robots range from repurposed bomb disposal robots trundling around on tank tracks, to robots that hang from the monorail attached to the ceiling of the tunnel in which the LHC is housed.

It was fascinating to learn how the robotics team take off-the-shelf parts and modify, adapt and re-purpose them with bespoke "stuff" to help them do their maintenance work.

For example, we were shown an electric drill you could have purchased from any conventional DIY store, that had been dismantled, reconfigured and reassembled to work while connected to a robot arm in the sometimes limited space in which such devices are needed.

How else are you going to unscrew nuts and bolts with a robot?

Well, it turns out you could use a Luke Skywalker like robotic hand.

When I enquired about its capabilities I was told it had many degrees of movement in all the joints one finds in a human hand. I wondered out loud if anyone had ever tried to play the piano with it, to which our host gave me a raised eyebrow and a thoughtful, "hmmm... that would be interesting".

Of course, there are your common "service droid" type robots that trundle around on wheels with a camera and arm attached to them. Even these are intricate and substantial bits of kit.

Both Will and I had a great time at CERN. A large part of the reason being Phil, Jo and their family's hospitality. As we were leaving for the airport Phil mentioned a film, called Particle Fever, that tells the story of how the folks at CERN confirmed the existence of the Higgs boson. On our return home Will and I watched it... and if you're looking for a film about particle physics, this is NOT it. Rather, it tells a great story and places CERN, and the work done there, into context.

At one point in the film, a physicist gives a presentation about the LHC (at a moment in time just prior to when it was first switched on) and fields a question from the audience. They are asked, "but what value is the work at CERN? (and by the way, I'm an economist)". The physicist giving the presentation is brutally honest and admits that he has no idea and the damn thing may not work.

This moment resonated with me.

It's not uncommon for folks to doubt the value of endeavours close to my heart such as classical music or philosophy. So hearing a physicist asked such a question made me think, "huh... so it happens to you folks too...".

I feel sad, disappointed and frustrated when I encounter people who can't imagine a world where economic value is not the only valuable outcome.

We don't make music, ponder philosophy nor try to comprehend the universe because such activities create economic value. We do them because they make life worth living, enlarge our world and connect us to something beyond ourselves. Any economic value is merely a welcome fortuitous side-effect. The Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman claimed that he didn't do physics to change the world or discover some grand unifying theory of everything, but just for the pleasure of finding things out.

Bravo CERN, it was a pleasure to find things out about the work you all do. I sincerely hope to return soon (with Will - he'd never forgive me if I left him at home).