Asynchronous Python

Python version 3.4 was recently released.

For me, the most interesting

update

was the inclusion of the

asyncio

module. The

documentation

states it,

...provides infrastructure for writing single-threaded concurrent code using coroutines, multiplexing I/O access over sockets and other resources, running network clients and servers, and other related primitives.

While I understand all the terminology from the documentation I don't yet

have a feel for the module nor do I yet comprehend when to use one

feature rather than another. Writing about this module and examining

concrete examples is my way to

grok

asyncio. I'll be concise and only assume familiarity with

Python.

So, what is asyncio?

It's a module that enables you to write code that concurrently handles asynchronous network based interactions.

What precisely do I mean?

Concurrency is when several things happen simultaneously. When something is

asynchronous it is literally not synchronised: there is no way to tell when

some thing may happen (in this case, network based I/O).

I/O (input/output)

is when a program communicates with the "outside world" and network based I/O

simply means the program communicates with another device (usually) on the

internet. Messages arrive and depart via the network at unpredictable times -

asyncio helps you write programs that deal with all these

interactions simultaneously.

How does it work?

At the core of asyncio is an

event loop.

This is simply code that keeps looping (I'm trying to avoid the

temptation of using a racing car analogy). Each "lap" of the loop (dammit)

checks for new I/O events and does various other "stuff" that we'll come onto

in a moment. Within the asyncio module, the

_run_once

method encapsulates a full iteration of the loop. Its documentation

explains:

This calls all currently ready callbacks, polls for I/O, schedules the resulting callbacks, and finally schedules 'call_later' callbacks.

A callback is code to be run when some event has occurred and

polling is discovering the status of something external to the

program (in this case network based I/O activity). When a small child

constantly asks, "are we there yet..?" on a long car journey, that's polling.

When the unfortunate parent replies, "I'll tell you when we arrive" they are

creating a sort of callback (i.e. they promise to do something when some

condition is met). The _run_once method processes the

I/O events that occurred during the time it took to complete the

previous "lap", ensures any callbacks that need to be run are done so

during this lap and carries out "housekeeping" needed for callbacks

that have yet to be called.

Importantly, the pending callbacks are executed one after the other - stopping the loop from continuing. In other words, the next "lap" cannot start until all the sequentially executed callbacks finish (in some sense).

I imagine you're thinking, "Hang on, I thought you said

asyncio works concurrently?" I did and it does. Here's the

problem: concurrency is hard and there's more than one way to do it. So it's

worth taking some time to examine why asyncio works in the

way that it does.

If concurrent tasks interact with a shared resource they run the risk of interfering with each other. For example, task A reads a record, task B reads the same record, both A and B change the retrieved record in different ways, task B writes the record, then task A writes the record (causing the changes made by task B to be lost). Such interactions between indeterminate "threaded" tasks result in painfully hard-to-reproduce bugs and complicated mechanisms required to mitigate such situations. This is bad because the KISS (keep it simple, stupid) principle is abandoned.

One solution is to program in a synchronous manner: tasks

executed one after the other so they have no chance to interfere with

each other. Such programs are easy to understand since they're simply

a deterministic sequential list of things to do: first A, then B,

followed by C and so on. Unfortunately, if A needs to wait for something, for

example, a reply from a machine on the network, then the whole program waits.

As a result, the program can't handle any other events that may occur

while it waits for A's network call to complete - in such a case,

the program is described as

"blocked".

The program becomes potentially slow and unresponsive - an unacceptable

condition if we're writing something that needs to react quickly to things

(such as a server - precisely the sort of program asyncio is

intended to help with).

Because asyncio is event driven, network related I/O is

non-blocking. Instead of waiting for a reply from a network call

before continuing with a computation, programmers define callbacks to be run

only when the result of the network call becomes known. In the meantime,

the program continues to respond to other things: the event loop keeps polling

for and responding to network I/O events (such as when the reply to our

network call arrives and the specified callbacks are executed).

This may sound abstract and confusing but it's remarkably close to how we make plans in real life: when X happens, do Y. More concretely, "when the tumble dryer finishes, fold the clothes and put them away". Here, "the tumble dryer finishes" is some event we're expecting and "fold the clothes and put them away" is a callback that specifies what to do when the event happens. Once this plan is made, we're free to get on with other things until we discover the tumble dryer has finished.

Furthermore, as humans we work on concurrent tasks in a similar non-blocking manner. We skip between the things we need to do while we wait for other things to happen: we know we'll have time to squeeze the orange juice while the toast and eggs are cooking when we make breakfast. Put in a programmatic way, execute B while waiting on the result of the network call made by A.

Such familiar concepts mean asyncio avoids potentially

confusing and complicated "threaded" concurrency while retaining the benefits

of strictly sequential code. In fact, the

specification for

asyncio states that callbacks are,

[...] strictly serialized: one callback must finish before the next one will be called. This is an important guarantee: when two or more callbacks use or modify shared state, each callback is guaranteed that while it is running, the shared state isn't changed by another callback.

Therefore, from a programmer's perspective, it is important to understand how asynchronous concurrent tasks are created, how such tasks pause while waiting for non-blocking I/O, and how the callbacks that handle the eventual results are defined. In other words, you need to understand coroutines, futures and tasks.

The asyncio module is helpfully simple about these

abstractions:

-

asyncio.coroutine- a decorator that indicates a function is a coroutine. A coroutine is simply a type of generator that uses theyield from,returnorraisesyntax to generate results. -

asyncio.Future- a class used to represent a result that may not be available yet. It is an abstraction of something that has yet to be realised. Callback functions that process the eventual result are added to instances of this class (like a sort of to-do list of functions to be executed when the result is known). If you're familiar with Twisted they're called deferreds and elsewhere they're sometimes called promises. -

asyncio.Task- a subclass ofasyncio.Futurethat wraps a coroutine. The resulting object is realised when the coroutine completes.

Let's examine each one of these abstractions in more detail:

A coroutine is a sort of generator function. A task defined

by a coroutine may be suspended; thus allowing the event loop to get on with

other things (as described above). The

yield from

syntax is used to suspend a coroutine. A coroutine can yield from

other coroutines or instances of the asyncio.Future

class. When the other

coroutine has a result or the pending Future object is realised,

execution of the coroutine continues from the yield from

statement that originally suspended the coroutine (this is sometimes referred

to as re-entry). The result of a yield from statement will be

either the return value of the other coroutine or the result of the

Future instance. If the referenced coroutine

or Future instance raise an exception this will be propagated.

Ultimately, at the end of the yield from chain, will be a

coroutine that actually returns a result or raises an exception (rather than

yielding from some other coroutine).

A helpful (yet not entirely accurate) metaphor is the process of calling a

customer support line. Perhaps you want to know why your order for goods

is late. The person at the end of the phone explains they can't continue with

your query because they need to check something with their accounts

department. They promise to call you back. This pause is similar to the

yield from statement: they're suspending the work while they

wait for something else, thus allowing you to get on with other stuff. At some

point, their accounts department will provide a result and the customer

support agent will re-enter the process of handling your query and when

they're done, will fulfil their promise and give you a call (hopefully with

good news about your order).

The important concept to remember is that yield from suspends

coroutines pending a result so the event loop is able to get on with other

things. When the result becomes known, the coroutine resumes.

The following example (like many of the examples in this post, it's an

annotated modification of code in the

Python documentation

on asyncio) illustrates these concepts by chaining coroutines

that ultimately add two numbers together:

"""

Two coroutines chained together.

The compute() coroutine is chained to the print_sum() coroutine. The

print_sum() coroutine waits until compute() is completed before it returns a

result.

"""

import asyncio

# Notice the decorator!

@asyncio.coroutine

def compute(x, y):

print("Compute %s + %s ..." % (x, y))

# Pause the coroutine for 1 second by yielding from asyncio's built in

# sleep coroutine. This simulates the time taken by a non-blocking I/O

# call. During this time the event loop can get on with other things.

yield from asyncio.sleep(1.0)

# Actually return a result!

return x + y

@asyncio.coroutine

def print_sum(x, y):

# Pause the coroutine until the compute() coroutine has a result.

result = yield from compute(x, y)

# The following print() function won't be called until there's a result.

print("%s + %s = %s" % (x, y, result))

# Reference the event loop.

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# Start the event loop and continue until print_sum() is complete.

loop.run_until_complete(print_sum(1, 2))

# Shut down the event loop.

loop.close()

Notice that the coroutines only execute when the loop's

run_until_complete method is called.

Under the hood,

the coroutine is wrapped in a Task instance and a callback is

added to this task that

raises the appropriate exception needed to stop the loop (since

the task is realised because the coroutine completed). The task instance is

conceptually the same as the promise the customer support agent gave to

call you back when they finished processing your query (in the helpful

yet inaccurate metaphor described above). The return value of

run_until_complete is the task's result or, in the event of a

problem, its exception will be raised. In this example, the result is

None (since print_sum doesn't actually return

anything to become the result of the task).

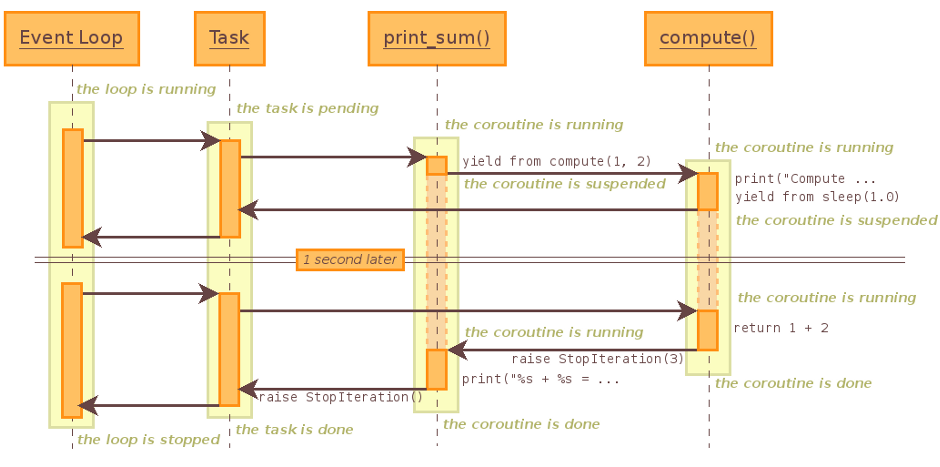

The following sequence diagram illustrates the flow of activity:

So far we've discovered that coroutines suspend and resume tasks in such a way that the event loop can get on with other things. Yet this only addresses how concurrent tasks co-exist through time given a single event loop. It doesn't tell us how to deal with the end result of such concurrent tasks when they complete and the result of their computation becomes known.

As has been already mentioned, the results of such pending concurrent

tasks are represented by instances of the async.Future class.

Callback functions are added to such instances via the

add_done_callback method. Callback functions have a single

argument: the Future instance to which they have been added.

They are executed when their Future's result eventually becomes

known (we say the Future is resolved). Resolution involves

setting the result using the set_result method or, in the case

of a problem, setting the appropriate exception via

set_exception. The callback can access the

Future's result (be it something valid or an exception) via the

result method: either the result will be returned or the

exception will be raised.

Another example (again, an annotated modification of code from the Python documentation) illustrates how this works:

"""

A future and coroutine interact. The future is resolved with the result of

the coroutine causing the specified callback to be executed.

"""

import asyncio

@asyncio.coroutine

def slow_operation(future):

"""

This coroutine takes a future and resolves it when its own result is

known

"""

# Imagine a pause from some non-blocking network based I/O here.

yield from asyncio.sleep(1)

# Resolve the future with an arbitrary result (for the purposes of

# illustration).

future.set_result('A result set by the slow_operation coroutine!')

def got_result(future):

"""

This function is a callback. Its only argument is the resolved future

whose result it prints. It then causes the event loop to stop.

"""

print(future.result())

loop.stop()

# Get the instance of the event loop (also referenced in got_result).

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# Instantiate the future we're going to use to represent the as-yet unknown

# result.

future = asyncio.Future()

# Wrap the coroutine in a task to schedule it for execution when the

# event loop starts.

asyncio.Task(slow_operation(future))

# Add the callback to the future. The callback will only be executed when the

# future is resolved by the coroutine. The future object is passed into the

# got_result callback.

future.add_done_callback(got_result)

# Run the event loop until loop.stop() is called (in got_result).

try:

loop.run_forever()

finally:

loop.close()

This example of futures and coroutines interacting probably feels awkward

(at least, it does to me). As a result, and because such interactions are so

fundamental to working with asyncio, one should use the

asyncio.Task class (a subclass of asyncio.Future)

to avoid such boilerplate code. The example above can be simplified and made

more readable as follows:

"""

A far simpler and easy-to-read way to do things!

A coroutine is wrapped in a Task instance. When the coroutine returns a result

the task is automatically resolved causing the specified callback to be

executed.

"""

import asyncio

@asyncio.coroutine

def slow_operation():

"""

This coroutine *returns* an eventual result.

"""

# Imagine a pause from some non-blocking network based I/O here.

yield from asyncio.sleep(1)

# A *lot* more conventional and no faffing about with future instances.

return 'A return value from the slow_operation coroutine!'

def got_result(future):

"""

This function is a callback. Its only argument is a resolved future

whose result it prints. It then causes the event loop to stop.

In this example, the resolved future is, in fact, a Task instance.

"""

print(future.result())

loop.stop()

# Get the instance of the event loop (also referenced in got_result).

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# Wrap the coroutine in a task to schedule it for execution when the event

# loop starts.

task = asyncio.Task(slow_operation())

# Add the callback to the task. The callback will only be executed when the

# task is resolved by the coroutine. The task object is passed into the

# got_result callback.

task.add_done_callback(got_result)

# Run the event loop until loop.stop() is called (in got_result).

try:

loop.run_forever()

finally:

loop.close()

To my eyes, this is a lot more comprehensible, easier to read and far

simpler to write. The Task class also makes it trivial to execute

tasks in parallel, as the following example (again,

taken from the Python documentation)

shows:

"""

Three tasks running the same factorial coroutine in parallel.

"""

import asyncio

@asyncio.coroutine

def factorial(name, number):

"""

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factorial

"""

f = 1

for i in range(2, number+1):

print("Task %s: Compute factorial(%s)..." % (name, i))

yield from asyncio.sleep(1)

f *= i

print("Task %s: factorial(%s) = %s" % (name, number, f))

# Instantiating tasks doesn't cause the coroutine to be run. It merely

# schedules the tasks.

tasks = [

asyncio.Task(factorial("A", 2)),

asyncio.Task(factorial("B", 3)),

asyncio.Task(factorial("C", 4)),

]

# Get the event loop and cause it to run until all the tasks are done.

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

loop.run_until_complete(asyncio.wait(tasks))

loop.close()

So far, all our examples have used the asyncio.sleep function

to simulate arbitrary amounts of time to represent the wait one might expect

for non-blocking network I/O. This is convenient for examples, but now that we

understand coroutines, futures and tasks we'd better examine how networking

fits into the picture.

There are two approaches one can take to network based operations: the high level Streams API or the lower level Transports and Protocols API. The following example (based on this original implementation) shows how a coroutine works with non-blocking network I/O in order to retrieve HTTP headers using the stream based API:

"""

Use a coroutine and the Streams API to get HTTP headers. Usage:

python headers.py http://example.com/path/page.html

"""

import asyncio

import urllib.parse

import sys

@asyncio.coroutine

def print_http_headers(url):

url = urllib.parse.urlsplit(url)

# An example of yielding from non-blocking network I/O.

reader, writer = yield from asyncio.open_connection(url.hostname, 80)

# Re-entry happens when the connection is made. The reader and writer

# stream objects represent what you'd expect given their names.

query = ('HEAD {url.path} HTTP/1.0\r\n'

'Host: {url.hostname}\r\n'

'\r\n').format(url=url)

# Write data out (does not block).

writer.write(query.encode('latin-1'))

while True:

# Another example of non-blocking network I/O for reading asynchronous

# input.

line = yield from reader.readline()

if not line:

break

line = line.decode('latin1').rstrip()

if line:

print('HTTP header> %s' % line)

# None of the following should be at all surprising.

url = sys.argv[1]

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

task = asyncio.async(print_http_headers(url))

loop.run_until_complete(task)

loop.close()

Note how, instead of yielding from asyncio.sleep, the

coroutine yields from the built in open_connection and

readline coroutines that handle the asynchronous networking I/O.

Importantly, the call to write does not block, but buffers the

data and sends it out asynchronously.

The lower level API should feel familiar to anyone who has written code using the Twisted framework. What follows is a trivial server (based on this example) that uses transports and protocols.

Transports are classes provided by asyncio to abstract

TCP,

UDP,

TLS/SSL

and

subprocess pipes.

Instances of such classes are responsible for the actual

I/O and buffering. However, you don't usually instantiate such classes

yourself; rather, you call the event loop instance to set things up (and

it'll call you back when it succeeds).

Once the connection is established, a

transport is always paired with an instance of the Protocol

class. You subclass Protocol to implement your own network

protocols; it parses incoming data and writes outgoing data by calling the

associated transport's methods for such purposes. Put simply, the

transport handles the sending and receiving of things down the wire, while

the protocol works out what the actual message means.

To implement a protocol override appropriate methods from the

Protocol parent class. Each time a connection is made (be it

incoming or outgoing) a new instance of the protocol is instantiated and

the various overridden methods are called depending on what network events

have been detected. For example, every protocol class will have its

connection_made and connection_lost methods

called when the connection begins and ends. Between these two calls one might

expect to handle data_received events and use the paired

Transport instance to send data. The following simple echo

server demonstrates the interaction between protocol and transport without

the distraction of coroutines and futures.

"""

A simple (yet poetic) echo server. ;-)

- ECHO -

Use your voice - say what you mean

Do not stand in the shadow

Do not become an echo of someone else's opinion

We must accept ourselves and each other

Even the perfect diamond

may have cracks and faults

A-L Andresen, 2014. (http://bit.ly/1nvhr8T)

"""

import asyncio

class EchoProtocol(asyncio.Protocol):

"""

Encapsulates the behaviour of the echo protocol. A new instance of this

class is created for each new connection.

"""

def connection_made(self, transport):

"""

Called only once when the new connection is made. The transport

argument represents the connection to the client.

"""

self.transport = transport

def data_received(self, data):

"""

Called when the client sends data (represented by the data argument).

"""

# Write the incoming data immediately back to the client connection.

self.transport.write(data)

# Calling self.transport.close() disconnects. If you want the

# connection to persist simply comment out the following line.

self.transport.close()

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

# Create the coroutine used to establish the server.

echo_coroutine = loop.create_server(EchoProtocol, '127.0.0.1', 8888)

# Run the coroutine to actually establish the server.

server = loop.run_until_complete(echo_coroutine)

try:

# Run the event loop forever, waiting for new connections.

loop.run_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

# Unless we get Ctrl-C keyboard interrupt.

print('exit')

finally:

# Stop serving (existing connections remain open).

server.close()

# Shut down the loop.

loop.close()

An example interaction with this server using netcat is shown below:

$ python echo.py &

[1] 7486

$ nc localhost 8888

Hello, World!

Hello, World!

$ fg

python echo.py

^Cexit

Yet, this only scratches the surface of asyncio and I'm

cherry-picking the parts that most interest me. If you want to find out more

the

Python documentation

for the module is a great place to start, as is

PEP 3156 used to

specify the module.

In conclusion asyncio feels like Twisted on a diet with the

added fun and elegance of coroutines. I've generally had good experiences

using Twisted but always felt uncomfortable with its odd naming conventions

(for example, calling the

secure shell implementation

"conch" is the world's worst programming pun) and I suffer from an uneasy

feeling that it exists in a slightly different parallel Pythonic universe.

Personally, I feel asyncio is a step in the right direction

because such a lot of the "good stuff" from Twisted has made it into the

core language in a relatively small and obvious module. I'm also looking

forward to using it in my own projects (specifically,

the drogulus).

As I become more adept at using this module I may write up more.

Image credits: Breakfast © 2010 Pankaj Kaushal under a Creative Commons License. Sequence Diagram © 2014 The Python Software Foundation.